No creature of the sea lives in a vacuum, they are all part of a system of resources, a machine of stones and shells, seaweeds and corals, dead matter, living matter and an assortment of nutrients and minerals dissolved in the water itself. A species is unlikely to survive or evolve unless it can be resourceful to some extent, from the hermit crabs who use empty snail shells to protect their soft abdomens to the corkring wrasse who use pieces of seaweed from various species to build their nests. Even the very act of hunting prey is a form of resource gathering, but, as always, there are some who go one step further and assume the abilities of their prey after consumption.

This can be found in nudibranchs, a group of gastropod molluscs that, unlike your typical sea snail or common garden snail (among others), are completely without an external shell, save for a temporary shell they only use as larvae. This should make them extremely vulnerable to predators and encourage them to hide away or make themselves inconspicuous by other means. Instead, many species have brightly coloured bodies to advertise their presence and, more importantly, advertise that they are toxic or extremely unpleasant to eat (a phenomenon is called ‘aposematism’). There’s a chance that the animal, nudibranch or otherwise, is bluffing about its toxic potential, but personally I wouldn’t risk it.

Their next most recognisable feature (in either nudibranch group) is the pair of rhinophores on their head, which they use to find food and mates, evade predators and other perceive their environment through chemical signals and cues.

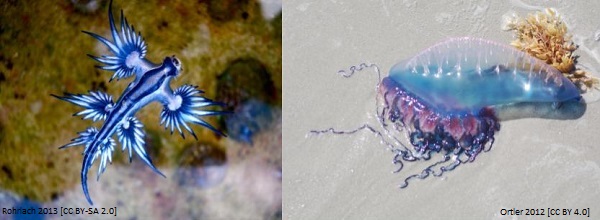

Nudibranchs are capable of producing their own defensive chemicals and storing them in various bumps, pockets or other specialised appendages depending on the species. But there is also evidence of them stealing toxins from sponges and the stinging cells of hydroids (cousins of jellyfish) after consumption. One particularly dramatic example involves the blue glaucus nudibranch (Glaucus atlanticus), also known as blue angels and blue dragons (among other common names). These stunning sea slugs dare to feed on probably the most dangerous hydroid of them all, the Portuguese man o’ war, and incorporate their deadly stings into their arsenal. Sometimes, these ‘blue dragons’ can travel together as ‘blue fleets’ which can end up washing ashore and stinging any swimmers and beachgoers who cross their path.

Some species also acquire the symbiotic zooxanthellae from their prey and then use their photosynthetic abilities as an extra food source. This was briefly mentioned in a previous article, but just to recap these zooxanthellae are tiny dinoflagellate algae which live inside the bodies of corals, anemones and other host animals, trading a portion of the food they produce via photosynthesis in exchange for protection and essential nutrients. But if their original host is consumed by a nudibranch, they may be invited to resume the account as before, just with a different benefactor.

One such species that farms zooxanthellae in this manner is Pteraeolidia ianthina, also known as blue dragons (not to be confused with Glaucus atlanticus and Glaucus marginatus). They have even evolved branches in their gut and body wall for keeping the captured zooxanthellae alive and functioning in ‘photosynthesising factories’. And the results speak for themselves, with one study recording their ability to survive for over 200 days without eating, while laden with stores of zooxanthellae.

These blue dragon nudibranchs (P. ianthina) mainly use Symbiodinium zooxanthellae to get the job done, but the exact species they use appears to vary, depending on where exactly in the Indo-Pacific region they are found. The simplest explanation would suggest that they are flexible, with different populations using whatever zooxanthellae are available to them and/or best suited to their environment. But there is an alternative, and somewhat more interesting explanation that some studies have alluded to, which suggests that the species P. ianthina may actually be a collection of species that look so similar that it’s very difficult to tell them apart. In biology, these are referred to as ‘cryptic species’ and, in this context, there are differences in their genetic makeup, the species of zooxanthellae they use and very slight differences in their morphology, such as the size and shape of some of their teeth.

It’s worth mentioning that nudibranchs are not the only marine animals who ‘acquire’ their tools and tricks from others. The neurotoxin used by pufferfish to scare away predators can be acquired from cultures of bacteria inside their intestines, which they in turn acquire from the food chain. Shipworms are another great example, they may use their sharp bivalve shells to burrow and eat their way through submerged wood (natural or otherwise), but it is their symbiotic bacteria that digests the wood into usable sugars. Others are not so subtle about it, such as the blanket octopus, who is known to rip off the tentacles of jellyfish and Portuguese man o’ wars and use them as weapons. Sometimes, you have to wonder how much of a species’ success is achieved by standing over the shoulders of their peers.

From a human perspective

Nudibranchs with zooxanthellae contained within their bodies are effectively, if temporarily, animal-plant hybrids. Something you’d expect to find in the realms of science fiction, DC comics characters like Poison Ivy and Swamp Thing come immediately to mind, yet it appears that fact can be just as strange as fiction. The sea slugs look otherworldly as it is, inspiring a host of creative common names including (but not limited to) spanish dancers, blue dragons, highland dancers, psychedelic hedgehogs, sea swallows, purple pineapples and living strawberries. Some of these names are associated with nudibranchs in general, sometimes in reference to a particular species.

Our curiosity for nudibranchs has even stretched to our palate, with some sources suggesting that they are roasted, boiled or eaten raw in Chile, Russia and Alaska and that the experience is like “chewing an eraser”. While eating sea slugs might not sound very appealing to some, it’s worth bearing in mind that different cultures have different histories and tastes when it comes to seafood. And even when nudibranchs are not literally on the end, they have encouraged an adventurous style when it comes to restaurants and cuisine. This is evidenced in no uncertain terms by a restaurant in New York that is literally called ‘Nudibranch’. Jeff Kim, head chef and co-founder of the restaurant, explained to ‘The New Yorker’ back in 2022 that he had observed the creatures whilst diving in Indonesia and that they proved “symbolic” during the brainstorming phase. This ultimately led to some playful dishes (mimicking the inherent playfulness of a nudibranch’s appearance) such as an attempt at the “most cauliflowery of cauliflower dishes.”

Leaning back into the world of science, a curious report dating all the way back to 1884 detailed the observations of a ‘Professor Grant’ (possibly Robert Edmond Grant). These included his work with two species of nudibranch that were identified as Eolis punctata (now called Facelina annulicornis) and Tritonia arborescens (now called Dendronotus frondosus). Both species appeared to produce sounds that “resemble very much the clink of steel wire on the side of a jar” which Grant believed to originate from their mouths. An interesting idea for sure, but there doesn’t seem to be any other studies out there, with any species of nudibranch, to corroborate these findings. That’s not to say that these observations are incorrect, only that we should be cautious until the results have been replicated.

So far we’ve covered examples of nudibranchs’ roles in science and human creativity, but the two don’t need to be polar opposites. Keeping to the 19th (and early 20th) century, these sea slugs were one of numerous groups of marine invertebrates to be replicated as glass models by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a father-son duo who created over 10,000 models between them. They were likely useful for demonstrating the appearance and intricacies of such creatures, especially the soft and squidgy ones, given their tendency to lose their colour and sometimes their stability, when preserved in alcohol. It would go some way to explaining how Leopold Blaschka in particular secured commissions all over the world. That and the Blaschkas’ patient hands, something we can safely assume from the small size of some of the models, as well as the intricate appendages, extremities and other sticky out bits from the animals they were replicating. Not to mention the other materials they would sometimes incorporate into their designs, such as wire, paint, glue and pieces from the original animals themselves (e.g. snail shells). The results really speak for themselves, with the uncanny accuracy of their models, compared to other makers of the time, coming from existing illustrations, expert consultations and from their own observations in the wild and live subjects they kept and used for reference. Alas, the family business finished when Rudolf Blaschka retired in 1938, leaving behind no apprentices (related or otherwise) to carry on their work.

Naturally, the best way to see nudibranchs, or any other sea creature for that matter, is alive and in their natural habitat. But if this isn’t an option, a Blashka model is a good second option. There’s also ‘Nudibranch Central’, a website and Facebook group run by Gary Cobb, a retired American expat living in Australia and who is arguably the biggest nudibranch fan on the planet. A reputation that is well founded based on his involvement in writing a nudibranch field guide back in 2006 and the six apps he designed for identifying nudibranchs in different regions of the world.

The common theme here is that nudibranchs can be such a great inspiration when encountered and observed in the right circumstances. It’s something the creatures of the ocean do very well with all their different colours and forms and functions within the interconnected web that is the natural world. It’s little surprise that there are people out there who have had their entire lives shaped by the ocean on their doorstep.

Sources

Wikipedia. 2024. Nudibranch. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nudibranch. Last accessed 17/05/2024

Geary. 2015. 10 things you did not know about Nudibranchs. https://atmosphereresorts.com/10-things-you-did-not-know-about-nudibranchs/#:~:text=At%20least%20two%20species%20of,a%20mate%2C%20or%20other%20reasons. Last accessed 10/05/2024

California Academy of Sciences. 2012. Sea Slug Senses Part I. https://www.calacademy.org/blogs/project-lab/sea-slug-senses-part-i. Last accessed 05/06/2024

McCullagh et al. One rhinophore probably provides sufficient sensory input for odour-based navigation by the nudibranch mollusc Tritonia diomedea

Dean and Prinsep. 2017. The chemistry and chemical ecology of nudibranchs

Oceana. Blue Glaucus. https://oceana.org/marine-life/blue-glaucus/. Last accessed 17/05/2024

Osterloff. Nudibranchs: How sea slugs steal venom. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/nudibranchs-psychedelic-thieves-of-the-sea.html. Last accessed 16/06/2024

Mares. 2017. The secret beauty of Nudibranchs. https://blog.mares.com/the-secret-beauty-of-nudibranchs-5221.html. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Rudman. 2000. Zooxanthellae in nudibranchs. http://www.seaslugforum.net/find/zoox3. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Animalia. PTERAEOLIDIA IANTHINA. https://animalia.bio/pteraeolidia-ianthina. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Wikipedia. 2024. Pteraeolidia ianthina. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pteraeolidia_ianthina. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Salleh. 2021. Bizarre ‘blue fleet’ blows onto Australia’s east coast. https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2021-02-13/bizarre-blue-fleet-blows-onto-australias-east-coast/13139456. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Rudman. 1998. Pteraeolidia ianthina (Angas,1864). http://www.seaslugforum.net/pteriant.htm. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Rudman. 1998. Solar-powered sea slugs. http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet/solarpow. Last accessed 10/05/2024

Hoegh-Guldberg and Hinde. 1986. Studies on a nudibranch that contains zooxanthellae. I. Photosynthesis, respiration and the translocation of newly fixed carbon by zooxanthellae in Pteraeolidia ianthina

Cella et al. 2016. A radical solution: the phylogeny of the nudibranch family Fionidae

Loh et al. 2006. Diversity of Symbiodinium dinoflagellate symbionts from the Indo-Pacific sea slug Pteraeolidia ianthina (Gastropoda: Mollusca)

Wilson and Burghardt. 2015. Here be dragons – phylogeography of Pteraeolidia ianthina (Angas, 1864) reveals multiple species of photosynthetic nudibranchs (Aeolidina: Nudibranchia)

Yorifuji et al. 2012. Hidden diversity in a reef-dwelling sea slug, Pteraeolidia ianthina (Nudibranchia, Aeolidina), in the Northwestern Pacific

Mizobata et al. 2023. The highly developed symbiotic system between the solar-powered nudibranch Pteraeolidia semperi and Symbiodiniacean algae

Burghardt et al. 2008. Symbiosis between Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) and various taxa of Nudibranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda), with analyses of long-term retention

Korshunova et al. 2019. Multilevel fine-scale diversity challenges the ‘cryptic species’ concept

Noguchi et al. 2006. TTX accumulation in pufferfish

Lee et al. 2000. A Tetrodotoxin-Producing Vibrio Strain, LM-1, from the Puffer Fish Fugu vermicularis radiatus

Waterbury et al. 1983. A cellulolytic nitrogen-fixing bacterium cultured from the gland of Deshayes in shipworms (Bivalvia: Teredinidae)

Yang et al. 2009. The complete genome of Teredinibacter turnerae T7901: an intracellular endosymbiont of marine wood-boring bivalves (shipworms)

Great Barrier Reef Foundation. Blanket Octopus. https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/animals/blanket-octopus#:~:text=These%20graceful%20creatures%20can%20adapt,toxic%20jellyfish%20as%20a%20weapon. Last accessed 15/06//2024

Frey. 2023. Meet the Blanket Octopus. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2023/01/05/meet-the-blanket-octopus/. Last accessed 15/06/2024

Gosse. 1884. Evenings at the microscope. Page 57-58. https://archive.org/details/eveningsatmicros00goss/page/56/mode/2up?view=theater&q=Professor+Grant. Last accessed 15/06/2024

Fan. 2022. Intrepid Playfulness at Nudibranch. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/06/20/intrepid-playfulness-at-nudibranch. Last accessed 15/06/2024

National Museums Scotland. Blaschka models. https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-sciences/blaschka-models/. Last accessed 18/06/2024

Robitzski. 2023. Slideshow: The Lifelike Glass Models of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. https://www.the-scientist.com/slideshow-the-lifelike-glass-models-of-leopold-and-rudolf-blaschka-70911. Last accessed 18/06/2024

Sullivan. 2024. Dive Into the Exotic World of Nudibranchs, the Spectacular Slugs of the Sea. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/dive-exotic-world-nudibranchs-spectacular-slugs-sea-180984013/. Last accessed 17/05/2024

Nudibranch Central. 2024. Species List: 2024-06-14 Toilet Block, Mooloolah River, La Balsa Park, Buddina, Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia. https://nudibranchcentral.blogspot.com/2024/06/species-list-2024-06-14-toilet-block.html. Last accessed 15/06/2024

Image sources

Heavydpj. 2021. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goniobranchus_Kuniei.jpg

Alexander R. Jenner. 2009. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nembrotha_chamberlaini_(AA1).jpg

Brocken Inaglory. 2007. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nudi_from_tidepool.jpg

Sylke Rohrlach from Sydney. 2013. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_dragon-glaucus_atlanticus_(8599051974).jpg

Brett Ortler. 2012. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalia_physalis_182283768.jpg

Sylke Rohrlach from Sydney. 2015. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_Dragon_Nudibranch-Pteraeolidia_ianthina_(16101797460).jpg

Bernard DUPONT from FRANCE. 2009. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sea_Slug_(Pteraeolidia_ianthina)_(6061874251).jpg

TanguyLoïs. 2023. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Facinela_(2)_-_Copie.jpg

Chichvarkhin A. 2016. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dendronotus_frondosus_(10.7717-peerj.2774)_Figure_7_(cropped).png

Bard Cadarn. 2016. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sea_Creatures_in_Glass.jpg

Mike Dickison. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nudibranch_Recliner_MRD_WCWPAL_07.jpg

For more bitesize content and ocean stories why not follow ‘Our world under the waves’ on…