by Matthew Norton

Antarctica is bitterly cold. It’s the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about the continent, along with the isolation, perpetual darkness for months on end and its lack of polar bears. But where there is hostility, there can also be the opportunity for nature to thrive. And it just so happens that the Antarctic Ocean (also known as the Southern Ocean) is teeming with life. Even beyond its border, the influence of those polar waters can be felt and utilised wherever the environment and evolution of a species deems it so. Such is the case with the Humboldt penguin, native to the coasts of Chile and Peru, which are furnished with nutrients from the Humboldt Current.

These penguins mainly dive (usually no more than 30 metres down) and partake in small, schooling fish like anchovies, herring, sardines, hake, smelt as well as the occasional squid. The nutrient rich waters keep these prey relatively abundant, but since natural selection is rarely kind to the complacent, Humboldt penguins will happily switch between prey types and/or travel long distances in search of profitable feeding grounds. Their sense of smell might indicate such areas while their eyes are tuned to the hunt itself. Nevertheless, both strategies hold the inherent risk of starvation, a risk that can be exacerbated if they have an egg to incubate, or a chick to feed.

If all goes well, then a single breeding pair will meet up twice a year to raise of clutch of young and ultimately form a strong, lifetime bonds.

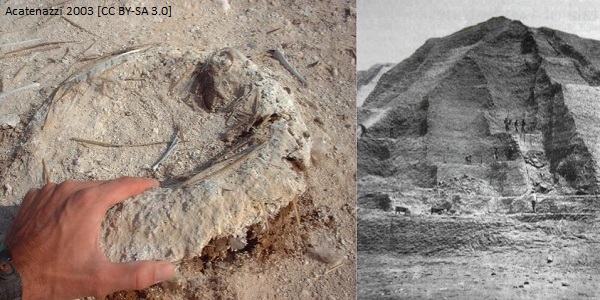

Similar to other penguins, Humboldt penguins need to nest and raise their young on land, their preferred breeding spots being on high slopes near the shore, ideally where there are rocky crevices to wedge their eggs, or guano deposits to burrow into. Surface nests can be made in a pinch, but even if the breeding colony is free from terrestrial predators (e.g. rodents, snakes, feral cats and dogs) there is still the risk of wind chill and overexposure to solar radiation (i.e. sunlight). To manage all that, just to keep those boisterous and demanding chicks out of trouble and hunt for food, the existence of predictable food sources nearby might just be the secret between life and death.

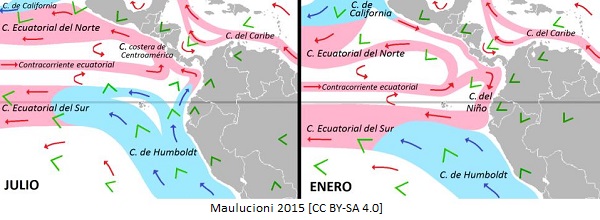

In theory, Humboldt penguins can breed at any time of the year and make extended foraging trips, alternating between daytime and night time feeds if necessary, to feed their chicks and meet their own nutritional needs. But a wise penguin would avoid going through the trouble of parenthood during an El Niño event. A naturally occurring phenomenon (though worsened by climate change) characterised by unusually high sea surface temperatures in a given stretch of ocean, more specifically an increase of 0.5°C for five successive three month seasons. An El Niño alone, or combined with the Southern Oscillation, an interannual fluctuation in atmospheric pressure, can have a devastating effect on the climate.

What does this have to do with the Humboldt penguin you might ask. There are lots of steps involved and factors to consider, but the short version is that an El Niño event can interfere with the Humboldt Current, dramatically reducing the supply of nutrients to the surface. And with less nutrients comes less plankton for fish to feed on, the fish that those penguins feed on. During a particularly strong event, they may simply abandon their nests so that they can keep themselves alive for the sake of future offspring that will have a better chance during easier times. It’s a pretty brutal case of sibling rivalry, but I guess that’s nature for you.

There are means by which the occurrence and severity of El Niño events can be gauged and predicted, such as the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). A useful, if foreboding early warning system that can predict major hits on commercial fish stocks while the altered climate affects the weather and agriculture on land.

Alas, one can only account for so much in this cruel, unpredictable world. Just last year (2023), an outbreak of avian flu caused the death of around 3,000 Humboldt penguins according to the Chilean Fisheries National Service. And then there’s the human factor to consider. Even when our intentions are benign, the mere sight of a human being can be distracting, stressful even to a penguin who can’t leave their nest. The effect might not even be that obvious according to one study, which found that a penguin’s heartbeat, specifically a penguin incubating an egg, can change if they see us from 150 metres away. A one-off incident might not do much, but in places that attract tourists, such as the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve in Chile, they could be stressed out on a regular basis, leading to harmful disturbances in their behaviour.

Such disturbances can be avoided, at least with wild populations, by visiting Humboldt penguins in zoos and aquariums instead. This obviously goes hand in hand with providing them with adequate care and enrichment so that the penguins can enjoy a good quality of life and engage in some of their natural behaviours, even within unnatural surroundings. This in turn requires extensive research to work out what chemicals to use, or not use, to clean their enclosures, whether they should be kept in single-species enclosures or be encouraged to mingle, whether live food is necessary to keep them stimulated, whether visitor viewing areas should be out in the open or restricted to ‘hides’ where they can be observed in secret and so on.

Back in March 2012 a one year old Humboldt penguin managed to escape from Tokyo Sea Life Park and eluded capture for over two months. Fortunately, “Penguin 337” seemed to be in good health upon their return, despite their lengthy stay into what was, for them, uncharted waters.

Interestingly, one study conducted at Fota Wildlife Park, Ireland, reported that their Humboldt penguins exhibited an increase in their feeding behaviour, preening behaviour, interactions with visitors and overall movement around their enclosure with the number of visitors watching them. It’s tempting to assume they actually enjoy the presence of their adoring fans, but the study could only report a positive correlation, which means that each measure increased with the number of visitors, which is not the same as suggesting that one causes the other. Science in general tends to be based on possibilities, probabilities and probably nots (depending on the available evidence), meaning you can only ever be 99.99999% sure a ‘fact’ is actually correct. This might explain why so many scientists go mad and turn into supervillains.

Nevertheless, the idea of encouraging contact between humans and (trained) Humboldt penguins has been tested by bringing them into care homes and hospices, something that would be inconceivable with wild penguins. In the United Kingdom, there are numerous news articles online covering such experiences with Pringle, Widget and Charlie from Heythrop Zoological Gardens. The benefits for the residents practically speak for themselves, with the animals bringing joy and wonder to those going through a difficult time. And the interactions appear to be well managed, assuming the articles are accurate, with keepers providing clear instructions on how to handle them.

Encouraging interactions between humans and animals, be they in the wild on in captivity, has been a contentious issue, and will probably remain so for the foreseeable future. Some praise the idea of engaging people with nature as a means to encourage positive conservation action, while others believe that zoos and aquariums shouldn’t exist at all. And these are merely two ends of the spectrum, with many fitting somewhere in between. It’s doubtful we’ll find an easy solution that pleases everybody because just like the animals we like to watch, by whatever means, we are all different people with different experiences and views on the world. The best I can do is offer my own personal opinion, which is that zoos and aquariums fulfil a vital role in conservation by engaging the general public with nature. So long as we look after the physical and mental health of the animals in our care and stay clear of species that cannot adapt to living a long and happy life in such an environment.

From a human perspective

The name we give to a species can say quite a bit about them, where they come from, what they look like, what they do in their day to day lives and so on. But sometimes they’re named after inspirational people including , but not limited to, celebrities, fictional characters and renowned scientists and naturalists. David Attenborough has at least forty to his name (at the time of writing), but for the Humboldt penguin we need to go further back in time to the Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859).

It’s little surprise there’s a mineral name after him, Humboldtine, which is typically found as yellow crystals (right).

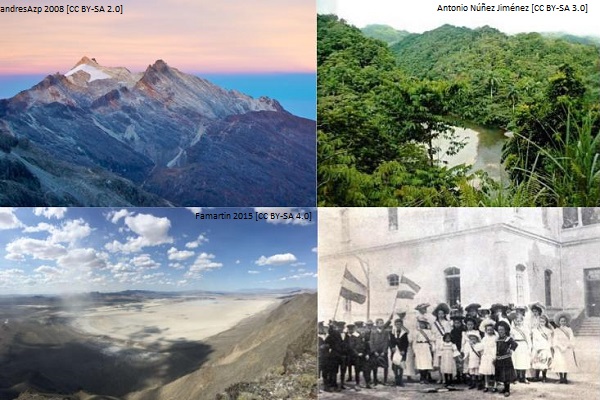

Humboldt achieved many extraordinary things during his life, starting with his five year expedition (1799-1804) around Central and South America, much of which was under Spanish colonial rule at the time. The data he collected, along with the fauna and flora he discovered and documented during his travels (over 6,000 miles worth) was so vast that it took years after his return to Europe to organise his research and field notes and publish it all. But during this time, he came to realise that every part of the natural world, including the living and non-living elements, was all connected. Even humans were not exempt from this interconnected world view, with Humboldt noticing how the draining of wetlands and clearing of forests was altering the landscape, making it arid and unproductive. This might seem obvious now (save for a select ignorant few), but compared to much of the prevailing scientific theory in the early 19th century, Humboldt really was ahead of his time.

His travels through the Spanish colonies also brought Humboldt’s attention to the damage colonialism was having on the indigenous population with ‘cash crops’ like sugar and indigo replacing food crops like maize. Meanwhile, trees were felled and dams were built, causing major problems for the rivers and lakes that farms relied on for irrigation. The treatment of indigenous labourers wasn’t much better, made to mine for precious metals and stones for little pay, made even more meagre by the overpriced goods they were forced to buy. Humboldt was also very much against slavery, which was reportedly the only point of contention when he made a detour to meet US president Thomas Jefferson at the White House. Nevertheless, Humboldt would later play a role in passing a law that granted freedom to any slave who entered Prussia’s borders.

Humboldt was also keen on sharing his theories and ideas, not to mention his efforts to support the science and popularise them across a wide range of social classes. This was evident during the time he spent living in Paris (1804-1827), where he delivered public lectures, collaborated with French scientists and illustrators and involved himself in salons, which in this specific context were centres of intellectual conversation. He was also known to use his experience, insight, influence, connections and even his (dwindling) fortune to support young, aspiring scientists.

This advocacy for science continued even after the threat of financial ruin forced Humboldt to return to Berlin at the behest of the Prussian King. There he continued to deliver public lectures as well as courses on physical geography at the University of Berlin. In the few years before his death, he also served as tutor to the crown prince of Prussia (among other royal duties), a position he used to introduce members of the royal family to the scientific methods and ideas of the time. And let us not forget the many letters of correspondence he sent and received during his lifetime, of which around 8,000 still exist. These included the letters he exchanged with a young Charles Darwin, one of Humboldt’s many admirers.

Even more detailed than his letters were the many books, essay and travel volumes Humboldt had published on botany, zoology, geology, mineralogy, astronomy, politics and so on. But perhaps his greatest work was also his last, a book to bring his concept of an interconnected natural world full circle. He said as much in writing: “I have the extravagant idea of describing in one and the same work the whole material world. All that we know today of celestial bodies and of life upon earth, from the nebular stars to the mosses on the granite rock.”

That work was ‘Kosmos’, also known as ‘Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe’. It started life as just one book, but ultimately swelled into five volumes, the last of which was incomplete at the time of Humboldt’s death. The first volume alone, which was finally published in 1845, was a sensational bestseller across Europe and translated into multiple languages. A fantastic outcome considering that his intention was for knowledge to be “the common property of mankind”. Would the popular science genre be what it is today without the contribution of Alexander von Humboldt?

Alas, even a connection to a legacy like this might not be enough to keep a species safe these days. The latest assessment by the IUCN classified the Humboldt penguin as ‘Vulnerable’ to extinction. Not ‘Endangered’ or ‘Critically Endangered’, yet, but in a modern world that threatens them with climate change, pollution, conflict with the fishing industry, invasive species and so on, we cannot afford to be complacent either. So as important as it is to look back on the past, it cannot be at the expense of the present. How else are we going to protect our planet, and our heritage, for the future?

Sources

Wikipedia. 2024a. Southern Ocean. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_Ocean. Last accessed 08/09/2024

Center for Biological Diveristy. HUMBOLDT PENGUIN. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/penguins/Humboldt_penguin.html. Last accessed 12/07/2024

Wikipedia. 2024b. Humboldt penguin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humboldt_penguin. Last accessed 12/07/2024

IUCN. 2020. Humboldt Penguin. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22697817/182714418. Last accessed 08/09/2024

Britannica. 2020. Humboldt penguin. https://www.britannica.com/animal/Humboldt-penguin. Last accessed 08/09/2024

Oceana. Humboldt Penguin. https://oceana.org/marine-life/humboldt-penguin/. Last accessed 08/09/2024

Owuor. 2018. What Is The Humboldt Current?. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-is-the-humboldt-current.html. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Culik. 2001. Finding food in the open ocean: foraging strategies in Humboldt penguins

Hennicke and Culik. 2005. Foraging performance and reproductive success of Humboldt penguins in relation to prey availability

De La Puente et al. 2013. Humboldt Penguin

Coffin et al. 2011. Odor-Based Recognition of Familiar and Related Conspecifics: A First Test Conducted on Captive Humboldt Penguins (Spheniscus humboldti)

Britannica. 2024. Guano. https://www.britannica.com/science/guano. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Wikipedia. 2024c. Guano. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guano. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Enfield. 2024. El Niño. https://www.britannica.com/science/El-Nino. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Britannica. 2012. Southern Oscillation. https://www.britannica.com/science/wind. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Ellenberg et al. 2006. Physiological and reproductive consequences of human disturbance in Humboldt penguins: the need for species-specific visitor management

Merco Press. 2023. Avian flu has caused the death of some 3,000 Humboldt penguins in Chilean coasts. https://en.mercopress.com/2023/10/23/avian-flu-has-caused-the-death-of-some-3-000-humboldt-penguins-in-chilean-coasts. Last accessed 12/07/2024

Tenikytė. 2024. 11 Adorable Humboldt Penguin Chicks Are Melting Hearts All Over The Internet. https://www.boredpanda.com/chester-zoo-celebrating-humboldt-penguin-chicks/. Last accessed 12/07/2024

Blay and Côté. 2002. Optimal conditions for breeding of captive humboldt penguins (Spheniscus humboldti): A survey of British zoos

Fernandez et al. 2021. The Effects of Live Feeding on Swimming Activity and Exhibit Use in Zoo Humboldt Penguins (Spheniscus humboldti)

Chiew et al. 2021. Effects of the presence of zoo visitors on zoo-housed little penguins (Eudyptula minor)

Smith et al. 2024. Effects of Enclosure Complexity and Design on Behaviour and Physiology in Captive Animals

Zhang et al. 2021. Impact of weather changes and human visitation on the behavior and activity level of captive humboldt penguins

Källström. 2020. Hägnutnyttjande och besökarpåverkan på Humboldtpingviner (Spheniscus humboldti)

Caston. 2024. Two Humboldt penguins bringing smiles to residents at a Lincolnshire care home. https://hellorayo.co.uk/hits-radio/lincolnshire/news/two-humboldt-penguins-bringing-smiles-at-lincolnshire-care-home/. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Jefford. 2024. Penguins visit care home for a flipping good time. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c720z69vekwo#:~:text=Care%20home%20residents%20were%20treated,at%20Cedar%20Mews%20in%20Leicester. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Heythrop Zoological Gardens. Care Home and Hospice Visits. https://www.heythropzoologicalgardens.org/care-home-and-hospice-visits. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Mills. 2021. Penguins waddle into care home ahead of new rules on visitor limits. https://metro.co.uk/2021/12/13/penguins-waddle-into-care-home-ahead-of-new-rules-on-visitor-limits-15766685/. Last accessed 09/08/2024

Jones. 2021. Penguins delight residents at Oxfordshire care home with Christmas visit. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/penguins-oxfordshire-humboldt-one-chile-b1975163.html

BBC News. 2012. Tokyo keepers catch fugitive Penguin 337. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-18202053. Last accessed 28/08/2024

Fair and Shersby. 2022. Animals and plants named after Sir David Attenborough. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/people/species-named-after-sir-david-attenborough. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Wulf. 2015. The invention of nature: The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt: The lost hero of science. ISBN. 978-1-84854-900-5

Kellner. 2024. Alexander von Humboldt. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alexander-von-Humboldt/Professional-life-in-Paris. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2019. Humboldt’s legacy. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0980-5. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Harvey. 2020. Who Was Alexander von Humboldt?. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/who-was-alexander-von-humboldt-180974473/. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Grupo Reforma. Colegio Alemán Alexander von Humboldt. https://gruporeforma.reforma.com/graficohtml5/club/colegiosemblematicos/alem%C3%A1n.html. Last accessed 28/08/2024

Mineralogy Database. Humboldtine Mineral Data. https://www.webmineral.com/data/Humboldtine.shtml. Last accessed 28/08/2024

Murphy and van Andel. 2024. Development of tectonic theory. https://www.britannica.com/science/plate-tectonics/Development-of-tectonic-theory. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Walls. 2016. Introducing Humboldt’s Cosmos. https://humansandnature.org/introducing-humboldts-cosmos/. Last accessed 24/07/2024

Rizk. 2010. Mare Humboldtianum Constellation region of interest. https://www.lroc.asu.edu/images/183. Last accessed 28/08/2024

Image sources

H. Zell. 2022. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spheniscus_humboldti_-_Zoo_am_Meer_-_Bremerhaven_01.jpg

Nrg800. 2010. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Humboldt_Penguin.png

Muséum de Toulouse. 2018. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spheniscus_humboldti_MHNT.ZOO.2010.11.43.14.jpg

Acatenazzi. 2003. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guano.jpg

Maulucioni. 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corrientes_ecuatoriales_del_Pac%C3%ADfico.png

Johannes Maximilian. 2020. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spheniscus_humboldti_in_Tiergarten_Sch%C3%B6nbrunn_24_July_2020_JM_(1).jpg

Joe Mabel. 2012. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WPZ_-_Humboldt_Penguin_group_01.jpg

Alan Daly. 2009. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spheniscus_humboldti_-Dublin_Zoo_-swimming-8a.jpg

Gzen92. 2019. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manchot_de_Humboldt_(Spheniscus_humboldti)_(3).jpg

Dick Culbert from Gibsons, B.C., Canada. 2013. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salix_humboldtiana_(8643642931).jpg

Petruss. 2012. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quercus_humboldtii_1.JPG

andresAzp from El valle de balas, Vzla. 2008. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PicoHumboldt.png

Antonio Núñez Jiménez. Date unknown. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alejandro_de_Humboldt_National_Park.jpg

Famartin. 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2015-04-18_15_36_28_Panorama_of_the_Humboldt_Sink_from_the_West_Humboldt_Range_in_Churchill_County,_Nevada.jpg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution.

For more bitesize content and ocean stories why not follow ‘Our world under the waves’ on…