by Matthew Norton

Every species found on land can trace their origins back to the ocean, the shining example being the first fish to crawl on land a long, long time ago. But some clearly decided that life beyond the sea was overrated and evolved towards an aquatic existence once more. Going so far as to sacrifice their ability to even support their weight on land, never mind walking on it (e.g. whales and dolphins). Others (e.g. seals and sea lions) opted to be more flexible, straddling the boundary between the sea and the land to varying degrees. And therein lies the precarious balance of pros and cons that can lead to some rather interesting outcomes.

From the world of marine reptiles we have the banded sea krait (also known as the yellow-lipped sea krait). They are snakes, and thus need to breathe air, but they’re also comfortable and more than capable in the water, often squeezing through the gaps between rocks and coral reefs in search of eels and other fish to hunt and consume. Even when outsized by their prey, they’re a force to be reckoned with, using their powerful venom to paralyse an eel before swallowing it whole (just like a snake on land). In aquarium conditions, they’ve been observed to release their prey after a strike and wait patiently for the venom to take effect. No point in taking undue risks with a meal that’s already theirs for the taking.

Their exact choice of prey can vary. The larger females (128cm long) will typically take a single conger eel per hunting trip, while the smaller males (75cm) need to hunt multiple smaller moray eels to satisfy their hunger. Naturally, those species of eel who are preyed upon by sea kraits have developed a greater tolerance to their venom to give them a fighting chance. A chance they might use to flee before being hit with a second dose, but this could throw them into the path of other reef predators looking to take advantage while they’re compromised. Sea kraits have even been known to form hunting alliances with yellow goatfish and blue trevally, as recently explained by Sir David Attenborough.

However, despite their prowess in hunting underwater, their link to the world above the waves is still there, holding on tight, compelling them to return to land to rest, drink freshwater and lay their eggs. Sea kraits even hold off digesting their latest catch until they are high and dry on the seaside. Something which has proved useful for sampling the abundance and diversity of anguilliform fishes (i.e. eels) in the habitats where these snakes hunt. Instead of diving and snorkelling in the water, hoping to find enough eels to get an accurate picture of what’s out there, some researchers have opted to encourage sea kraits to regurgitate their catches instead. Providing a reliable census of eels within their local vicinity.

Meanwhile, the so-called ‘true’ sea snakes, which have produced 64 recognised species, compared to the poultry eight species of sea krait, are decidedly more specialised for actually living underwater, rather than just hunting. There are some similarities between the two groups (despite having evolved towards the aquatic/semi-aquatic lifestyle independently of each other), such as a paddle-shaped tail for underwater swimming. But the sea snakes also boast small scales around their belly to keep the body shape compressed and streamlined, glands in the floor of their mouth to excrete excess salt and an ability to breathe through their skin. In the annulated sea snake (also known as the blue-banded sea snake) research has found a highly vascularised area (i.e. an area with lots of vessels, in this case blood vessels) between the snout and the top of the head. This is thought to provide a kind of oxygen hotline between the skin and the brain to keep the latter topped up.

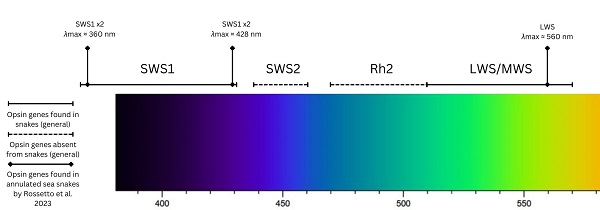

Curiously, the eyesight of certain sea snakes also seems to have diverged from their land dwelling cousins. Staying with the annulated sea snake, a study published in 2023 suggests that they may have ‘re-evolved’ an ability to see certain colours, colours that were lost to them some time after their ancestors first emerged from the ocean, specifically through the loss of certain opsin genes. The light detecting proteins generated from these strands of genetic code are what makes photoreceptor cells work, allowing the eyes of humans, snakes (and many others) to see.

There are various types of opsins, and subtypes within those types, all sensitive to different wavelengths (and thus different colours) of light. All of which can be modified, retained or lost depending on how a species evolves through the millennia, which in itself can be determined by their environment, the prey they hunt, the predators they must avoid and a whole host of other considerations that I won’t go into here. Suffice to say that modern snakes have lost the SWS2 and Rh2 opsin gene types, effectively rendering them colour-blind to light wavelengths between 437-510nm, or violet/blue to green, colours of light that maintain a strong presence in the ocean they had originally left behind.

But in the annulated sea snake, this study found four versions of the SWS1 opsin gene, compared to just the single version found in four other snake species (including a sea krait and another sea snake). Two of them were sensitive to ultraviolet light (peaking at 360nm), while the other two (peaking at 428nm) were geared closer to the violet/blue area of the spectrum. Combined with other opsin types, such as the LWS opsin gene (peaking at 560nm), the snake’s eyes could, perhaps, combine all that visual information to partially plug that gap in their colour vision, like a scab starting to form around a cut. This still being a recent study, there are other theories to be explored and more research to be done. Although an earlier study (published in 2020) looked at various sea snake species and suggested a sensitivity shift from ultraviolet to blue light.

As demonstrated by the the relevant opsin genes found in annulated sea snakes (as reported by Rossetto et al. 2023) and the wavelengths at which the absorption of photons is as its strongest (λmax). In other words, the wavelength (and colour) of light that each opsin gene is most sensitive to.

In any case, moving from one habitat to another, even if only on a part-time basis, would require a species to change, and then drive further change in the species that descend from them. There were always going to be genetic casualties along the way, sometimes genes, sometimes whole populations, species and species groups are rendered obsolete while everything else continues to evolve. It’s a process that is unlikely to remember what used to work in the distant past, or preserve anything that might work in a thousand generations’ time. Survival and reproduction in the moment, that’s what evolution by natural selection works off. But every now and then, a familiar idea (if only familiar to the outside observer looking in) can present itself. Proving that, if the means and the incentive is there, the wheel can be reinvented again and again.

From a human perspective

There is a myth out there that sea snakes are harmless to humans because their mouth is too small to deliver a bite. While not exactly true, their fangs are often quite small and the venom isn’t always delivered during an attack. That said, the venom is still extremely dangerous. For example, the banded sea krait is thought to be one of the most toxic snake species out there, with a venom that is around 10 times more potent than that of a rattlesnake. The venom itself is a neurotoxin, which can interfere with the nervous system, causing paralysis (similar to what can happen if you eat an improperly prepared pufferfish). It can be fatal if critical muscles, like those of the respiratory system, are affected.

Luckily, sea snakes are usually benevolent around us humans, showing virtually no interest unless provoked. Sometimes, this can be accidental, such as when people find them tangled in their fishing nets (not always well documented in remote fishing communities). Sometimes, these potentially perilous interactions can come about through good old fashioned foolishness, or at least a lack of awareness of the danger they can pose. This is what happened in 2017, when Suzanne Parrish, an Australian tourist on New Caledonia, a group of small islands in the Pacific, handled and played with a “seemingly cute snake” she found on the beach, only to later learn how badly it could have ended. In her defence, she shared the images and context of her mistake to warn others.

Furthermore, sea kraits are not only common on New Caledonia, they are thoroughly embraced. They enjoy a certain level of protection from a number of marine reserves within the peninsula’s waters and have seeped their way into the local pop-culture as towels, bags, toys, cartoon drawings and so on. The residents call them “tricot rayé”, which translates to mean “striped sweater” or possibly “striped T-shirt”. A name that makes a blazing amount of sense when you hear about children playing with the snakes, even draping them around their necks as if they’re wearing a striped scarf. Yet only one death by snake bite has ever been recorded on the island, a statistic made even more remarkable when you account for the small bays and corresponding coastlines that can be beset with tourists as well as locals.

In a travel blog article published by Susan Scott in 2014, she claimed to have witnessed a yellow-faced sea krait crawl around the lobby of a hotel on Maitre Island (a tiny islet that can be found off the south coast of New Caledonia’s main island). Not too surprising, considering that a 2009 study, which caught and released New Caledonian sea kraits (which do indeed have yellow faces) and blue-lipped sea kraits, found that the former were better tree climbers and more inclined to venture inland. Yet this specific encounter seemed to inspire mutual indifference between the snake and the hotel workers.

Moving away from New Caledonia, whilst also skimming across the northern edges of Australia (keeping south of Papua New Guinea along the way), we arrive at the Indonesian island of Bali. Specifically a rock formation just off its coast, on which Pura Tanah Lot stands (“Pura” being the Balinese word for temple). Built as a series of sea temples in the 16th century by Dang Hyang Nirartha, a Javanese priest who played a significant role in establishing Hinduism in Bali, its purpose was to worship Bhatara Segara, the sea god. But to protect the temple from evil intruders, Nirartha was believed to have created a sea snake/s to guard the base of the tiny islet.

But despite the appreciation they inspire, sea snakes (by any definition) should be handled with care. Dr David Gower, researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, likely kept this in mind when he joined an expedition in Northwest Australia. An expedition which involved taking tissue samples from around 70 sea snakes. Incidentally, there is another study out there which Dr Gower co-authored, along with several colleagues, that found evidence of light sensitive cells in the tails of certain species. Something to take into account if you’re planning to sneak up on one for whatever reason, scientific or otherwise.

Others, understandably, prefer to keep their hands to themselves, observing and recording sea snakes and sea kraits from a distance. Going back to New Caledonia, a place where a fair amount of research has been conducted, I’d like to draw particular attention to a research paper published in 2019. Its title, and I swear I’m not making this up, was Grandmothers and deadly snakes: an unusual project in “citizen science”, referring to a group of women in their sixties and seventies (all residents of New Caledonia) who took part in the project. By simply photographing any snake they happened to spot during their recreational dives, they collected data on over 140 greater sea snakes over a 25 month period. Far more than was previously estimated to be living at the survey site, estimates likely made by professional snake researchers who had the specific qualifications and experience, but were left lacking when it came to manpower and resources. Enter the citizen scientist.

All in all, some pretty compelling evidence that sea kraits and sea snakes are not the human killing machines that the potency of their venom might suggest. Most likely because hardly anything about them evolved with humans in mind. After all, we are far from their natural prey, or natural predators. Yet we are becoming an increasingly unavoidable part of their lives. Earlier I mentioned how some species can be specialised to a particular habitat, whereas others are more flexible, all to varying degrees. Against purely natural pressures, there will be risks and rewards to be found with every strategy within this spectrum. But against humanity’s unrelenting influence, the generalists would have the edge in my opinion. That said, they will have just as much to gain once we start properly easing off the gas pedal and giving nature the chance to recover.

Sources

Oceana. Banded Sea Krait. https://oceana.org/marine-life/banded-sea-krait/. Last accessed 15/11/2024

Davies. A deep dive into sea snakes, sea kraits and their aquatic adaptations. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/sea-snakes-sea-kraits-and-their-aquatic-adaptations.html. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Britannica. 2022. sea snake. https://www.britannica.com/animal/sea-snake. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Wikipedia. 2024. Sea krait. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_krait. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Arkive. 2012. Black-banded sea krait (Laticauda semifasciata). https://web.archive.org/web/20121008080803/http://www.arkive.org/black-banded-sea-krait/laticauda-semifasciata/image-G78940.html. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Radcliffe and Chiszar. 1980. A descriptive analysis of predatory behavior in the yellow lipped sea krait (Laticauda colubrina)

Shetty and Shine. 2002a. Sexual divergence in diets and morphology in Fijian sea snakes Laticauda colubrina (Laticaudinae)

Heatwole and Powell. 1998. Resistance of eels (Gymnothorax) to the venom of sea kraits (Laticauda colubrina): a test of coevolution

Aquarium of the Pacific. Banded Sea Krait. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/banded_sea_krait. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Ineich et al. 2007. Anguilliform fishes and sea kraits: neglected predators in coral-reef ecosystems

Reed et al. 2002. Sea Kraits (Squamata: Laticauda spp.) as a Useful Bioassay for Assessing Local Diversity of Eels (Muraenidae, Congridae) in the Western Pacific Ocean

Shetty and Shine. 2002b. Philopatry and Homing Behavior of Sea Snakes (Laticauda colubrina) from Two Adjacent Islands in Fiji

Beatson. 2020. Yellow-bellied Sea Snake. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/reptiles/yellow-bellied-sea-snake/. Last accessed 11/12/2024

Oceana. Olive Sea Snake. https://oceana.org/marine-life/olive-sea-snake/. Last accessed 11/12/2024

Palci et al. 2019. Novel vascular plexus in the head of a sea snake (Elapidae, Hydrophiinae) revealed by high-resolution computed tomography and histology

Rossetto et al. 2023. Functional duplication of the short-wavelength-sensitive opsin in sea snakes: evidence for reexpanded color sensitivity following ancestral regression

Hagen et al. 2023. The evolutionary history and spectral tuning of vertebrate visual opsins

The Reptile Database. Hydrophis cyanocinctus DAUDIN, 1803. https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Hydrophis&species=cyanocinctus. Last accessed 05/12/2024

UCLA – Chemistry and Biochemistry. Illustrated Glossary of Organic Chemistry – Lambda max. https://www.chem.ucla.edu/~harding/IGOC/L/lambda_max.html#:~:text=Illustrated%20Glossary%20of%20Organic%20Chemistry,the%20spectrum’s%20y%2Daxis). Last accessed 05/12/2024

Simões et al. 2020. Spectral diversification and trans-species allelic polymorphism during the land-to-sea transition in snakes

Coghill. 2024. Aussie woman pictured ‘playing with death’ on beach holiday. https://au.news.yahoo.com/aussie-woman-pictured-playing-with-death-beach-holiday-025959238.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAALB2dZjWT5KGgtipZpOaCbIsVtBMC3do0rSCcG8_P6d4BKiLZ0jdR-y0oQc9G-gP1KKSuDXCPlikd_GpiOr2hIF6Lr0EhONqp8HroBnR3Ys6JBiLKBID3ud6EFivfDvV7IcRuPi1dmlPoQ1VGanPMihljbAAg3C_V1Sr-0cVkx68. Last accessed 05/12/2024

Susan Scott. 2014. Friendly, sedate sea snakes can be lethal but rarely are. https://www.susanscott.net/friendly-sedate-sea-snakes-can-be-lethal-but-rarely-are/. Last accessed 10/11/2024

Jagot. 2023. The photographer’s eye: The sea-snakes of New Caledonia: Whether ashore or at sea, you can observe them… but don’t disturb them!. https://www.multihulls-world.com/articles-catamaran-trimaran/the-photographer-s-eye-the-sea-snakes-of-new-caledonia-whether-ashore-or-at-sea-you-can-observe-them-but-don-t-disturb-them. Last accessed 07/12/2024

United Nations. 2024. New Caledonia. https://www.un.org/dppa/decolonization/en/nsgt/new-caledonia. Last accessed 07/12/2024

Smartravler. 2024. New Caledonia. https://www.smartraveller.gov.au/destinations/pacific/new-caledonia#:~:text=Safety-,We%20continue%20to%20advise%20reconsider%20your%20need%20to%20travel%20to,may%20increase%20at%20short%20notice. Last accessed 07/12/2024

Brischoux and Bonnet. 2009. Life history of sea kraits in New Caledonia

Wonderful Indonesia. Tanah Lot. https://www.indonesia.travel/uk/en/destinations/bali-nusa-tenggara/tanah-lot.html#:~:text=Tanah%20Lot%20temple%20was%20built,the%20temple%20from%20evil%20intruders. Last accessed 05/12/2024

Dougherty. 2018. How the Balinese See the Sea: Interpretations of Oceanic Power

Greener Bali. Temples In Bali Explained -The Guide For Beginners. https://greenerbali.com/temples-in-bali-explained-the-guide-for-beginners/#Tanah_Lot_Temple. Last accessed 05/12/2024

Crowe-Riddell et al. 2019. Phototactic tails: evolution and molecular basis of a novel sensory trait in sea snakes

Goiran and Shine. 2019. Grandmothers and deadly snakes: an unusual project in “citizen science”

Davey. 2019. Snorkelling grandmothers uncover large population of venomous sea snakes in Noumea. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/24/snorkelling-grandmothers-uncover-large-population-of-venomous-sea-snakes-in-noumea. Last accessed 07/12/2024

Image sources

Luluchouette. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_colubrina_175170642.jpg

Melianie_and_max. 2017. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_colubrina_9098984.jpg

Bernard DUPONT from FRANCE. 2001. [CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Banded_Sea_Krait_(Laticauda_colubrina)_returning_to_the_sea_(14638010061).jpg

Cheng Te Hsu. 2020. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_colubrina_92201993.jpg

Christian Gloor from Wakatobi Dive Resort, Indonesia. 2013. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_laticaudata_(9960391413).jpg

Richard Ling. 2006. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aipysurus_laevis.jpg

Keesgroenendijk. 2021. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hydrophis_platurus_118933110.jpg

Aloaiza. 2008. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pelamis_platura,_Costa_Rica.jpg

Christinelmiller. 2020. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Transcription_and_Translation.png

Melianie_and_max. 2017. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_colubrina_9098967.jpg

Cheng Te Hsu. 2019. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_laticaudata_57928895.jpg

Lisa Bennett. 2013. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laticauda_laticaudata_1839211.jpg

TUBS. 2011. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_Caledonia_in_its_region_(special_marker).svg

Jakub Hałun. 2022. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pura_Tanah_Lot,_Bali,_Indonesia,_20220827_1009_1162.jpg

Grayswoodsurrey. 2014. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TanahLot_2014.JPG

Okkisafire. 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tanah_Lot_odalan_ritual.jpg

Arabsalam. 2011. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pura_Tanah_Lot_Bali17.jpg

Claire Goiran. 2019. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Two_grandmothers_diving_around_a_greater_sea_snake_Hydrophis_major,_photographing_the_snake%27s_tail_for_identification_-_Ecs22877-fig-0003-m.jpg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution.