by Matthew Norton

Things are often not what they appear to be. An animal can be anchored in one place like a plant, the patterns on a small fish can greatly exaggerate their size and ferocity, and the name of a species can be misleading towards their true nature (e.g. Eurasian oystercatchers). Even the group that a species belongs to can be questioned, with their appearance and lifestyle leaning heavily towards one classification while actually belonging to another. You’d swear the natural world was trying to confuse us on purpose.

Fire corals, all belonging to the Millepora genus, are a curious example of this phenomenon. Found in virtually all tropical and subtropical oceans, except for their odd absence around Hawaii, they are colonial animals with each ‘coral’ made up of many microscopic polyps or zooids (a widely used term for the members of colonial organisms, see Bryozoan article). Each polyp/zooid is encased with the fire coral’s smooth exoskeleton, specifically within little pores at the surface which are connected to a network of hollow channels below. The principle is somewhat similar to the honeycomb structure of a beehive.

And just like a colony of bees, there is some division of labour among the polyps/zooids of a fire coral, with the pores in which they reside being named accordingly. Within the gastropores you will find the short and plump gastrozooids, which are primarily concerned with engulfing and processing food for itself and for the wider colony. Meanwhile, the dactylzoooids, found within the dactylpores, possess long, thin hairs that are packed with nematocysts (stinging cells) for capturing prey and defending the colony.

Fire corals can also include outside contractors in the form of microscopic zooxanthellae, with which they build symbiotic (i.e. mutually beneficial) relationships. The fire coral provides protection to the zooxanthellae in exchange for a portion of the food they produce via photosynthesis.

So far, so coral-like, right? Which makes it all the more extraordinary that fire corals actually belong to a group of animals called Hydrozoans (also known as hydroids and hydrocorals). As part of the Cnidarian phylum (phyla being the big, umbrella groups by which all organisms are divided and classified, second only to kingdoms and domains), they are related to true corals, along with anemones, jellyfish and box jellyfish among others. In evolutionary terms, hydrozoans are more closely related to jellyfish than corals, but the variety they demonstrate is so baffling that such comparisons are far from easy to see.

When you account for this variety and their similarities to corals, anemones, jellyfish (and so on), classifying the different hydrozoan groups becomes an arduous task, with estimates of the total number of hydrozoan species seeming to vary depending on where the information is coming from. The one unifying feature they share (as far as I can tell) is that a hydrozoan’s gonads (the reproductive organs) are synthesised from their epidermal tissue (the equivalent of their outer skin layer), whereas all other cnidarians seem to derive it from their gastrodermal tissue (the lining of their very basic stomach).

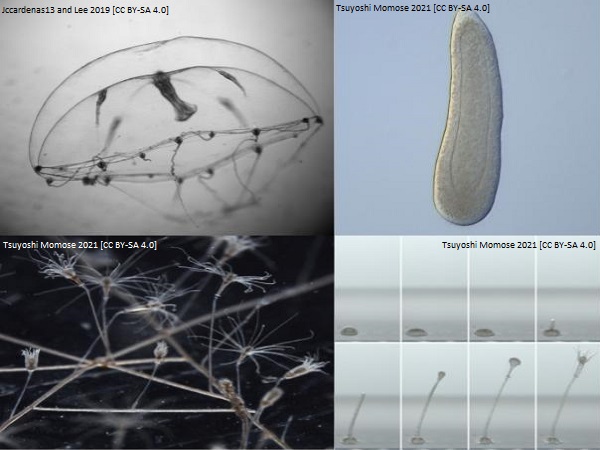

The life cycles of hydrozoans (and other cnidarians for that matter) can also alternate between medusa (jellyfish-like) and polyp (anemone/coral-like) stages. And between these forms, there are intermediate larval stages, such as the planula larvae produced when going from medusa to polyp. But even this broad guide must allow for the modifications enacted by many species where either stage can be suppressed or bypassed entirely. For example, some prevent their medusae from completing its development, keeping them attached to the pre-existing polyp, sometimes leaving them with little more than their gonads (reproductive organs).

And there is further complexity to be found in the asexual methods of reproduction. With any given hydrozoan, there may be ‘buds’ emerging from (depending on what they possess) the stem, stolon (the equivalent of plant roots sticking into the ground) or from specialised collections of tissue. These ‘buds’ can include podocysts, which are bunches of cells packed with all the necessary organic compounds and other bits and pieces, and frustules, which can resemble planula larvae. In both cases, these ‘buds’ can transform into new polyps when the time is right and the environmental conditions are suitable for such an undertaking. Then again, not every opportunity is planned in advance, but even the ripped off fragments of a hydrozoan colony can settle and grow again.

Some hydrozoans also possess regenerative abilities that are so incredible they should be limited to science fiction. And yet, slice and dice a Hydra polyp and each small piece can regenerate like it was nothing (albeit with some limitations). And then there’s Turritopsis dohrnii, the so-called ‘immortal jellyfish’, famous for its ability to skip backwards from medusa to polyp, effectively reverting to their younger self, rather than following the life cycle in the right direction. If they weren’t without a brain, one could argue that these hydrozoans have some vanity issues.

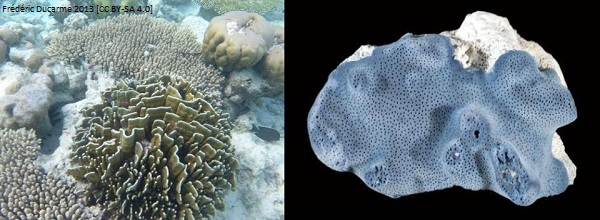

It should also be acknowledged that the fire corals have achieved some considerable variety within their ranks. The shape and structure of their exoskeletons alone, as well as the ‘branching tree’ shape shown earlier, can also grow as sheets (similar to lettuce corals) and encrust themselves over hard surfaces like rock, shells and dead coral, adopting the shape of their foundations along the way. But they all execute sexual reproduction by releasing their medusae (also called hydromedusae) into the water, representing the genetic potential of their colony in the few hours of life they are afforded. Long enough for each medusa to release its cargo of eggs and sperm into the water, where (hopefully) they will mix together.

But for all this diversity among the hydrozoans, much of what’s been mentioned thus far also applies to other cnidarian groups. Even in the most extensive and diverse family trees, there is almost always some aspect of their design, some means of survival and/or reproduction that most, if not all members have in common. And beyond that, there are adaptations out there which have evolved multiple times in multiple groups independently (the evolution of wings in birds, bats and insects being the classic example). It would seem that, under the right circumstances, a good idea can transcend time and distance.

From a human perspective

A fire coral’s sting, as the name suggests, can be incredibly painful. Any swimmer, snorkelling or diver whose exposed skin brushes against them (presumably by accident) is likely to experience a burning sensation that can last hours, a rash that can last for several days, disappear, and then reappear days, maybe even weeks later. The exact symptoms can vary depending on the susceptibility of the victim and how deep the venom penetrates (e.g. if it gets into an already open cut). In some cases, the stung tissue can become damaged and necrotic, paving the way for an infection.

That said, the fire coral would be least of your problems if there’s a deadly cone snail in the mix (right).

A particularly serious case was reported in 1992, involving a 52 year old woman who scraped her right wrist on some fire coral and later experienced muscle weakness and had difficulty moving her right arm and shoulder, along with a strange ‘lump’. Seeking medical attention around four months later, the sting was found to have caused paralysis in her right serratus anterior muscle (roughly located around the shoulder and ribs). But after around eight months of physical therapy, the strength of this muscle returned to “near normal”.

There is more to a fire coral than just its sting however. Like true corals, their exoskeletons provide structure and complexity, a place where each branch, sheet, outcrop, nook and cranny is a little bit different, each creating a slightly different habitat where other species might thrive. Fire corals may also, potentially, play a role in limiting the damage the modern world is doing to coral reefs, by resisting the effects of global warming, hurricanes, diseases and other stressors that are endangering the true corals. Their apparent ability to recover quickly from damage and seizing the chance to replace seaweeds and grow over dead corals could very well preserve a reef’s structure should the need arise. It won’t be exactly the same as a proper coral reef, but it’ll likely be better than nothing.

But let’s not get complacent either. Every species on this planet has their breaking point, even those who appear to be widespread and incredibly resilient to an ever changing world. Some species of fire coral don’t even have that luxury, being endemic (i.e restricted to one area) and thus vulnerable to local disasters. One species, Millepora boschma, believed to be endemic to the Gulf of Chiriquí in Panama, was officially named, described and presumed to be extinct in the same research paper from 1991. It was observed back in the 1970s, but a severe ENSO event (see Humboldt penguin article) lasting from 1982 to 1983 was thought to have wiped them out, with only dead colonies found in the following eight years. Fortunately, this obituary was short lived, with five live colonies of M. boschma being found off the coast of Uva Island, also in the Gulf of Chiriquí, in 1992.

This particular close call may have been a primarily natural occurrence (so far as we know), but it still demonstrates how some species may not come back after a truly devastating event, even if the range of its impact is limited. Other species of fire coral, or other populations of M. boschma, may swoop in to fill the power vacuum, but that’s a dangerous game for us to play.

Still, given recent developments in global politics (at the time of writing), it’s easy to be pessimistic about our chances of preserving the world’s coral reefs, and the biodiversity contained within. But it doesn’t mean that such efforts are in vain. Take the #StopAdani movement for example, which was aimed at the Adani Group, a multinational conglomerate based in India, who proposed the Carmichael coal mine in Australia back in 2010. A project that gained approval after approval, despite being temporarily stalled in 2015 due to a government official not properly considering the mine’s impact on endangered species.

By 2018, the environmental impacts of the proposed mine (including, but not limited to the threat it posed to coral reefs) prompted a huge protest march. The pressure inflicted by this march, and the wider #StopAdani movement, caused many of the other companies associated with the mine (e.g. banks and construction firms) to back out. Yet the mine still went ahead, with construction starting in 2019 and the political willpower behind the project remaining strong until at least 2022. But from major delays and poor returns on their investments to huge losses on the stock market and the arrest warrant issued for billionaire owner Gautam Adani over bribery and fraud allegations, the ride for Adani has not been easy. Not even close.

With coal being one of the worst, if not the worst fossil fuel you could burn, it’s not hard to imagine what inspired the “Coral not coal” message.

Think of it this way. In nature, sometimes the trick to surviving a predator encounter is not to escape outright, but to make yourself so difficult to overcome that it’s hardly worth the effort. So when arguing against those who seek to wreck the environment for their own ends, even when outright victory is not possible, we can always make the process extremely difficult and exhausting for them.

And no matter what, we always have the ability to make noise, to really press the ocean’s importance in our lives (and vice versa). How this supposedly separate world is really a part of us, and a part we cannot afford to lose or degrade into a broken shadow of its former self. To quote Brian Blessed, a fellow animal lover and possibly the loudest man in the universe: ”Don’t let the b*****ds get you down!”

Sources

Wikipedia. 2024. Fire coral https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fire_coral. Last accessed 24/01/2025

Lamar University: Department of Biology. 2011. Fire Coral. https://www.lamar.edu/arts-sciences/biology/study-abroad-belize/marine-critters/marine-critters-1/fire-coral.html#:~:text=Habitat,or%20the%20edges%20of%20reefs. Last accessed 13/02/2025

Britannica. Dactylozooid. https://www.britannica.com/animal/cnidarian. Last accessed 24/01/2025

Borneman. Venomous Corals: The Fire Corals. https://www.reefkeeping.com/issues/2002-11/eb/. Last accessed 13/02/2025

Al-Lihaibi et al. 2002. Long-chain wax esterns and diphenylamine in fire coral Millepora dichotoma and Millepora platyphylla from Saudi Red Sea Coast

Margulis and Chapman. 2010. Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth. ISBN. 978-0-12-373621-5

LibreTexts: Biology and Boundless. 32.5.4: Class Cubozoa and Class Hydrozoa. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Map%3A_Raven_Biology_12th_Edition/32%3A_Animal_Diversity_and_the_Evolution_of_Body_Plans/32.05%3A_Eumetazoa-_Animals_with_True_Tissues/32.5.4%3A_Class_Cubozoa_and_Class_Hydrozoa#:~:text=Out%20of%20all%20cnidarians%2C%20cubozoans,are%20derived%20from%20epidermal%20tissue. Last accessed 29/01/2025

OpenEd CUNY. Phylum Cnidaria: Class Hydrozoa. https://opened.cuny.edu/courseware/lesson/746/student-old/?task=5. Last accessed 29/01/2025

Shikina and Chang. 2018. Comparative Reproduction, in

Encyclopedia of Reproduction (Second Edition). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/hydrozoa. Last accessed 29/01/2025

Wikipedia. 2025. Hydrozoa. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydrozoa#Systematics_and_evolution. Last accessed 29/01/2025

Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Life Cycle of Jellyfish. https://www.vims.edu/bayinfo/jellyfish/lifecycle/. Last accessed 13/02/2025

Ferraioli. 2019. Clytia hemisphaerica. https://evocell-itn.eu/2019/01/25/clytia-hemisphaerica/. Last accessed 27/03/2025

National Biodiversity Data Centre. Clytia hemisphaerica. https://species.biodiversityireland.ie/profile.php?taxonId=16070. Last accessed 27/03/2025

Dumont. 2009. Cnidaria (Coelenterata), in Encyclopedia of Inland Waters. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/frustule#:~:text=The%20nonparasitic%20freshwater%20cnidarians%20may,cilia%2C%20eventually%20becomes%20fixed%20on. Last accessed 13/02/2025

Boero et al. 1992. On the origins and evolution of hydromedusan life cycles (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa)

Boero et al. 1997. Diversity of hydroidomedusan life cycles: ecological implications and evolutionary patterns

Fujisawa. 2003. Hydra regeneration and epitheliopeptides

The Biologist. 2016. Everlasting life: the ‘immortal’ jellyfish. https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist-features/everlasting-life-the-immortal-jellyfish. Last accessed 29/01/2025

Divers Alert Network. Fire Coral. https://dan.org/health-medicine/health-resources/diseases-conditions/fire-coral/. Last accessed 24/01/2025

Moats. 1992. Fire coral envenomation

Khalid and Azimpouran. 2023. Necrosis. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557627/. Last accessed 13/02/2025

Karunaharamoorthy. 2023. Serratus anterior muscle. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/serratus-anterior-muscle. Last accessed 24/01/2025

Pennisi. 2022. How does Caribbean fire coral thrive as others vanish? https://www.science.org/content/article/how-does-caribbean-fire-coral-thrive-others-vanish. Last accessed 24/01/2025

Guzman et al. 2019. Warm seawater temperature promotes substrate colonization by the blue coral, Heliopora coerulea

De Souza et al. 2017. Contrasting patterns of connectivity among endemic and widespread fire coral species (Millepora spp.) in the tropical Southwestern Atlantic

Reeflex.net. Millepora laboreli Fire coral. https://www.reeflex.net/tiere/15651_Millepora_laboreli.htm. Last accessed 24/01/2025

de Weerdt and Glynn. 1991. A new and presumably now extinct species of Millepora (Hydrozoa) in the eastern Pacific

Glynn and Feingold. 1992. Hydrocoral species not extinct

ABC News. 2015. Approval of Adani’s $16 billion Carmichael coal mine in Queensland’s Galilee Basin set aside by Federal Court. https://web.archive.org/web/20150825130300/http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-05/federal-court-overturns-approval-of-adanis-carmichael-coal-mine/6673734. Last accessed 25/02/2025

Australian Mining. 2019. Adani starts construction at Carmichael project. https://web.archive.org/web/20200902201114/https://www.australianmining.com.au/news/adani-starts-construction-at-carmichael-project/. Last accessed 25/02/2025

Gulliver. Australian Campaign Case Study: Stop Adani, 2012 – 2022. https://commonslibrary.org/australian-campaign-case-study-stop-adani-2012-2022/#Campaign_Outcomes. Last accessed 25/02/2025

#StopAdani. 2021. Eight years behind schedule, Adani’s Carmichael Coal mine is operating, but not as planned. https://www.stopadani.com/what_adani_has. Last accessed 25/02/2025

#StopAdani. 2024. Adani Group has lost $55 billion on the stock market. https://www.stopadani.com/adani_group_has_lost_55_billion_on_the_stock_market. Last accessed 25/02/2025

#StopAdani. 2025. US SEC seeks India’s help in Adani fraud probe. https://www.stopadani.com/us_sec_seeks_indias_help_in_adani_fraud_probe. Last accessed 25/02/2025

Holmes. 2018. Brian Blessed: one of a kind. https://www.bigissuenorth.com/features/2018/06/brian-blessed-one-kind/#close. Last accessed 27/03/2025

Image sources

Nhobgood Nick Hobgood. 2010. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Millepora_alcicornis_(Branching_Fire_Coral).jpg

Fernando Herranz Martín. 2005. [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Millepora_alcicornis,_dactylozoides.jpg

Bernard Picton. 2014. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tubularia-indivisa.jpg

Bernard Picton. 2014. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Halecium-muricatum.jpg

Brett Ortler. 2012. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalia_physalis_182283768.jpg

Catriona Munro, Stefan Siebert, Felipe Zapata, Mark Howison, Alejandro Damian-Serrano, Samuel H. Church, Freya E.Goetz, Philip R. Pugh, Steven H.D.Haddock, Casey W.Dunn. 2018. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apolemia_sp.jpg

Derek Keats from Johannesburg, South Africa. 2011. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elasmobranch_egg_cases_on_a_hydrozoan_at_Gota_Sorayer,_Red_Sea,_Egypt_-SCUBA_(6369654837).jpg

Brocken Inaglory. 2004. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fire_corals.JPG

Chaloklum Diving. 2006. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acropora_millepora,_table-coral-feeding.jpg

Jccardenas13 and Elizabeth Lee, PhD. 2019. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adult_side.jpg

Tsuyoshi Momose. 2021. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clytia_hemisphaerica_day2_planula.jpg

Tsuyoshi Momose. 2021. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Metamorphosis_of_Clytia_hemisphaerica.jpg

Tsuyoshi Momose. 2021. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clytia_hemisphaerica_polyp_colony.jpg

Frank Fox. 2012. [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mikrofoto.de-Hydra_15.jpg

Bachware. 2016. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turritopsis_dohrnii.jpg

Pannini. 2009. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fire_coral.jpg

FunkMonk. 2024. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Millepora_exaesa_holotype_specimen_and_bottle_encrusted_by_the_species.jpg

Tim Sheerman-Chase from Tabuk, Arabie Saoudite. 2007. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Textile_Cone_Shell_on_Fire_Coral.jpg

James St. John. 2010. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Millepora_complanata_(bladed_fire_corals)_(San_Salvador_Island,_Bahamas)_1_(16083655635).jpg

Derek Keats from Johannesburg, South Africa. 2010. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fire_coral,_looking_up_(6163169487).jpg

Frédéric Ducarme. 2013. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heliopora_coerulea_Maldives.jpg

Pannini. 2009. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fire_coral.jpg

John Englart from Fawkner, Australia. 2018. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coral_not_coal_-_Melbourne_climate_march_for_our_future_-_-stopAdani_-_IMG_3855_(46229071941).jpg

John Englart from Fawkner, Australia. 2018. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coral_not_coal_-_Melbourne_climate_march_for_our_future_-_-stopAdani_-_IMG_3923_(45505894254).jpg