by Matthew Norton

The ocean today is a beautifully diverse world, full of stunning habitats, wonderfully weird phenomena and species who have originated from many diverging walks of life. Even so, they only represent the minutest fraction of what has lived throughout the history of life on planet Earth. A history that began at least 3.5 billion years ago (according to the earliest known fossils), or maybe 4.1 billion years ago (according to other strands of evidence). Dinosaurs are, in general, the most well known animals who are no longer alive today, despite the best efforts of Richard Attenborough, but in the sea, few prehistoric predators have inspired as much awe as the Megalodon shark.

Thought to have gone extinct around 3.6 million years ago, megalodons are often pictured as great white sharks, but scaled up in size. A single fossilised tooth by itself can be the size of your hand (around 7 inches long), compared to the great white’s tooth, which is about the length of your finger (around 3 inches).

A shark’s teeth, including those from extant (still living) species, can tell us more about the animal than just its sheer size. Their shape, for example, can tell us a lot about how they bite and what prey they take. Strong, flat teeth are likely employed in crushing hard shelled animals like crabs and molluscs. Long, needle-point teeth are better equipped for gripping small to medium sized fish, along with other slippery prey. And triangular, serrated teeth is the way to go when slicing and tearing large prey into more manageable chunks.

With megalodons, you rarely get anything but the teeth to work with. This is because the skeleton of any shark, whether ancient or modern day, is made out of cartilage rather than bone. This is great for reducing weight (cartilage being about half as dense as bone) and enhancing flexibility and swimming speed. But if you want to be preserved as a fossil, the process works far better with harder materials like bones and shells.

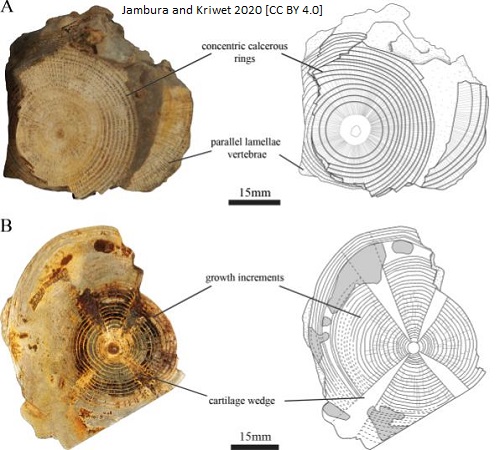

That said, it can happen, with the very occasional discovery of fossilised placoid scales, also known as dermal denticles (the tooth-like scales found in sharks and rays) as well as fragments of cartilage and segments of their vertebrae (also made out of cartilage). All of which can be used to make educated guesses about the animal’s biology and interactions with the world around them.

Vertebrae in particular can be imprinted with ‘growth rings’ that indicate the age of the animal. The technique is most famously used to age trees, particularly species temperate regions, where the growing conditions vary throughout the year. Cut a tree down (or better yet wait for it to fall due to natural causes) and look into the trunk and you’ll see alternating light and dark rings that show its growth in spring/early summer and later summer/autumn respectively, with each pair of light and dark rings equating to one year of growth. But the technique can also be applied to the ear bones (otoliths) of bony fish, the vertebrae of modern day sharks and, as it turns out, the vertebrae of ancient sharks. Which led to a 2025 study inferring that newborn megalodon sharks were somewhere between 3.6 to 3.9 metres long.

But no matter how impressive, or intuitive, a tool may seem, it still needs some sort of a calibration, a reference point to make your measurements make sense. This is where modern day species can come in as an analogue, or proxy species that we assume to be similar (within a given margin of error) to the ancient species we are studying, allowing us to fill in the blanks. This idea has cropped up in previous articles, such as the modern day Nautiluses acting as proxies for extinct ammonites, but with megalodons, the proxy species of choice has often been, unsurprisingly, the great white shark.

‘It’s a fish, all right,’ said Hooper. He was still visibly excited. ‘And what a fish! Damn near megalodon.’

Alas, such assumptions should always be used with a hint of caution. Not least because the scientific name for the megalodon shark has gone from Carcharodon megalodon to Otodus megalodon, suggesting the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is not as close a relative as first thought. Such changes to the ‘accepted’ lineages of a species can occur quite often as new evidence comes to light to challenge our previously solid conclusions.

Furthermore, there is also evidence to suggest that great white sharks would have major problems supporting themselves and swimming properly if their size was scaled up to the size of a megalodon. A more slender body, like that of a lemon shark, would be considerably more practical and probably a more accurate representation of what a megalodon shark actually looked like. Yet great whites, though sometimes used alongside other species, are still used as a proxy species simply because we don’t have anything better.

This makes for a somewhat uncomfortable demonstration of how difficult it can be to get things right with species that no human has ever actually seen first-hand, whether they be aquatic or terrestrial (i.e. land based). One especially informative example arose from a study published in the year 2000, which made some very bold claims regarding the fossilised remains of an ornithischian dinosaur. After using a CT scanner, among other techniques, they suggested that the specimen not only contained a fossilised heart, but that it also contained four chambers, like those of mammals and birds, rather than the less efficient three-chambered heart of a reptile. One might have dared to believe that these dinosaurs were also warm-blooded, again like today’s birds and mammals. But less than a year later, a different research group took another look at the same fossil and came to the conclusion that this ‘heart’ was actually ironstone. Yet another group examined the same fossil around ten years later, using more advanced CT scans, X-rays and electron microscope images, and concluded that this ‘heart’ was made of cemented grains of sand.

These were likely embarrassing developments for the original researchers, but the course corrections that followed (and not just in this one case) were only possible through the continued work of palaeontologists, paleobiologists and scientists in other related fields. In some instances, they may inspire or guide the development of new techniques and tools along the way. For example (bringing the conversation back to megalodons), a study published in 2022 generated a 3-D model from an especially well preserved megalodon fossil. This allowed the researchers to infer that they were likely transoceanic hunters capable of consuming prey large enough to fuel long migrations, whilst travelling at a cruising speed that was faster than any shark species alive today.

All in all, megalodons may not have been the supermassive great white sharks we thought them to be. But they were still incredible animals who will continue to inspire awe and the imaginations of many. Just like the dinosaurs who once roamed the land and the pterodactyls who soared through the sky.

From a human perspective

I love sharks. Big or small, alive or extinct, few animals in the sea get the blood pumping like they do. It’s one of a number of reasons I’ve made them the star of this, the 50th article to be published on Our world under the waves. A milestone that, by happy accident, has closely coincided with the 50th anniversary of Jaws (the film, not the original novel). A film synonymous with horror, summer blockbusters and multiple robotic sharks that proved exceptionally problematic to work with.

Unlike that legendary, and fictional, great white shark, megalodons have never swum in the sea at the same time as humans (so far as we know). Yet there’s been no shortage of films to explore how that might go down, with varying degrees of quality.

***WARNING: Spoilers ahead***

The Meg (2018) for example. It’s got Jason Statham versus a massive shark, I mean what more do you want? Not much judging by the nearly $530 million the film grossed at the box office worldwide, despite its modest reviews. The plot was fairly straightforward, following a research team as they dive from their underwater facility down to a hidden realm at the bottom of the ocean, from which they accidentally lead not one, but two megalodons back to the surface, ready to wreak havoc. Both sharks arguably had a rough deal from the start though, given Statham’s history of not losing on-screen fights, sometimes literally being written into the contract.

And then, before the likes of Godzilla vs Kong, or Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice, there was Mega Shark versus Giant Octopus (2009), a hilariously schlocky film that served little purpose beyond easy entertainment, which is fair enough (I’d take it over reality TV any day). And it clearly worked, given the series of (somehow) even more bizarre sequels is spawned, pitting the titular shark against a “Crocosaurus”, a “Mecha shark” and “Kolussus”, a giant doomsday robot.

For me, the stand out moment of absurdity from the original entry in the series is when the titular megalodon was able to launch itself out of the ocean and bring down a commercial airplane with its teeth. A scene I specifically looked up again online, just to make sure it wasn’t my imagination playing tricks on me. To be fair, we’ve never actually had the chance to observe the limits of a breaching megalodon, assuming they could thrust themselves out of the water at all. But that kind of range seems far fetched to say the least.

And before all that, you had Shark Attack 3: Megalodon (2002), another dumb fun film with bad writing and even worse special effects. Any Doctor Who fans watching this film (whatever your reasons may be) will likely recognise John Barrowman in the starring role. And he has been pretty open about the fact that he did the film for the money, even going so far as to say “it bought me my first place” during an appearance on the BBC Two series QI. But the film as a whole, like the Mega Shark series, had become a cult classic due, in part, to its incredible awfulness.

Whatever the critical reception may be, all of these films have one very Jaws-like element in common. They all suggest that if megalodons were to reappear today, they would be bloodthirsty, human-killing machines. But given how unsuitable we are to the large predatory sharks that are around today (e.g. great white sharks, tiger sharks, bull sharks) this is very unlikely to be the case for something as colossal as a megalodon.

Unfortunately, no movie studio (to my knowledge) has portrayed megalodons in a more sympathetic light. But sharks in general have enjoyed the occasional moment of (relatively) favourable representation.

In the world of animation you have Shark Tale (2004), perhaps the most star-studded film here, with the likes of Will Smith, Robert De Niro, Angelina Jolie, Jack Black and so on. While De Niro portays a more menacing shark gangster, his son Lenny (voiced by Jack Black) embodies a much friendlier archetype, being both vegetarian and the friend of a cleaner erase Oscar (Will Smith). Lenny goes so far as to help Oscar pursue his dreams of fame and fortune when he falsely claims credit for the death of Frankie, Lenny’s brother. Though hardly realistic by any stretch, it nevertheless proves that positive representation of sharks is possible.

But long before Shark Tale, there was Mako: The jaws of death (1976), a rather bizarre film that was released the year after Jaws on what appeared to be a much lower budget. There’s still plenty of shark biting action (though strangely no actual mako sharks), but most of the time it’s the sharks retaliating against shark hunters, fishermen and other humans seeking to exploit their kind. And in the midst of it all there’s Sonny, a character with some sort of psychic connection that allows him to sharks.

At first, Sonny is somewhat hopeful that he can change people’s attitudes toward sharks by renting out some of fishy friends to the local aquarium and a bar with an inbuilt show tank. But when he uncovers the abuse they’re being put through, he takes brutal action, sometimes dolling the punishment himself, sometimes facilating the vengeance of the sharks around him.

Overall, the film is not a perfect advocate for sharks, especially when you account for the notice plastered onto the opening shot, praising the underwater camera crew who “risked their lives to film the shark sequences in this motion picture.” But at the very least, it was a genuine departure from portraying sharks as mindless killing machines.

It’s also worth briefly touching upon an even older Italian / French film called Tiko and the shark (1962), which tells the story of Ti-Koyo, a young boy who befriends a baby shark, before introducing him to his girlfriend Diana (later his wife) before rekindling their friendship a decade later. It certainly feels massively ahead of its time, yet it has been argued that it could have gone further. Specifically by Leo Pestelli, a critic writing for the daily newspaper La Stampa, who criticised the film for focussing too much on Ti-Koyo romance with Diana, at the expense of his relationship with the shark.

But despite all the efforts to portray sharks in a different light, it’s easy to see why they make for such good movie monsters. Jaws very much set that standard in stone, becoming a major pop culture sensation in the 50 years since, as demonstrated by its three sequels, of very variable quality, the video game adaptation Jaws Unleashed (2006), released for the PlayStation 2, Xbox and PC and a prequel novel focussed on Quint’s backstory. And let’s not forget the seemingly endless variety of merchandise including, but not limited to, T-shirts, clocks, board games, posters, custom Lego sets and key rings.

I also recently had the pleasure of watching the play “The shark is broken” at the Theatre Royal in Plymouth. For those who don’t know, the play portrays the three main lead actors from Jaws (with Robert Shaw played by his own son, Ian Shaw) and everything they did to pass the time, and get on each other’s nerves while the crew dealt with various calamities behind the scenes. As mentioned earlier, such calamities often involved “Bruce” the robotic shark (and his ‘stunt doubles’) constantly breaking down. It just goes to show that even the film’s flaws and issues have proven to be worth exploring. A status that few others have achieved.

The problem arises when we fail to disseminate fiction from reality and believe in the killer shark (however unintentionally) that has proven to be such a guaranteed box office success. But things are getting better, and more and more people are coming to understand that sharks are sentient, thinking creatures and that they form critical roles in ecosystems across the world under the waves. Here’s hoping that trend continues for the next fifty years.

Sources

Center for Near Earth Object Studies. NEO Basics. https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/about/life_on_earth.html. Last accessed 25/05/2025

Sarchet. 2024. We now know that life began on Earth much earlier than we thought. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2444811-we-now-know-that-life-began-on-earth-much-earlier-than-we-thought/. Last accessed 25/05/2025

Davis. 2025. Megalodon: The truth about the largest shark that ever lived. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/megalodon–the-truth-about-the-largest-shark-that-ever-lived.html. Last accessed 26/04/2025

FossilEra. Megalodon Vs. Great White Tooth Size. https://www.fossilera.com/pages/megalodon-vs-great-white-tooth-size#:~:text=There%20have%20only%20been%20a,hard%20to%20confuse%20the%20two. Last accessed 18/06/2025

Chetan-Welsh. What can shark teeth tell us?. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-can-shark-teeth-tell-us.html. Last accessed 25/05/2025

Natural History Museum. Do sharks have bones?. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/quick-questions/do-sharks-have-bones.html. Last accessed 25/05/2025

Benchley. 1974. Jaws. ISBN 978-1-4472-2003-9

NOAA. Discover Your World with NOAA: Be a Tree Ring Detective. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/dyw-tree-detective.html. Last accessed 07/06/2025

Rajalakshmi. 2024. Growth rings in fish give clues about fluctuations in climate over decades. https://news.arizona.edu/news/growth-rings-fish-give-clues-about-fluctuations-climate-over-decades. Last accessed 07/06/2025

Hutching. 2006. Shark vertebra. https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/5318/shark-vertebra. Last accessed 07/06/2025

Stoller-Conrad. 2017. Tree rings provide snapshots of Earth’s past climate. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2540/tree-rings-provide-snapshots-of-earths-past-climate/. Last accessed 07/06/2025

Jambura and Kriwet. 2020. Articulated remains of the extinct shark Ptychodus (Elasmobranchii, Ptychodontidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Spain provide insights into gigantism, growth rate and life history of ptychodontid sharks

Hone et al. 2018. Evidence for the Cretaceous shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli feeding on the pterosaur Pteranodon from the Niobrara Formation

Amalfitano et al. 2019. Large deadfalls of the ʻginsuʼ shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz, 1835)(Neoselachii, Lamniformes) from the Upper Cretaceous of northeastern Italy

Pimiento et al. 2010. Ancient nursery area for the extinct giant shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama

Shimada. 2002. The relationship between the tooth size and total body length in the white shark

Shimada et al. 2017. A new elusive otodontid shark (Lamniformes: Otodontidae) from the lower Miocene, and comments on the taxonomy of otodontid genera, including the ‘megatoothed’ clade

Sternes et al. 2024. White shark comparison reveals a slender body for the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae)

Fisher et al. 2000. Cardiovascular evidence for an intermediate or higher metabolic rate in an ornithischian dinosaur

Rowe et al. 2001. Dinosaur with a heart of stone

Cleland et al. 2011. Histological, chemical, and morphological reexamination of the “heart” of a small Late Cretaceous Thescelosaurus

Black. 2011. Willo the Dinosaur Loses Heart. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/willo-the-dinosaur-loses-heart-93712793/. Last accessed 07/06/2025

Cooper et al. 2022. The extinct shark Otodus megalodon was a transoceanic superpredator: Inferences from 3D modeling

IMDb a. The Meg. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4779682/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

The Business Standard. 2020. The Rock, Vin Diesel’s ‘Fast and Furious’ contract say they can’t lose fights. https://www.tbsnews.net/glitz/rock-vin-diesels-fast-and-furious-contract-say-they-cant-lose-fights-113596. Last accessed 08/05/2025

IMDb b. Mega Shark Vs Giant Octopus. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1350498/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

Wikipedia. 2025. Mega Shark (film series). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mega_Shark_(film_series). Last accessed 08/05/2025

IMDb c. Mega Shark vs. Kolossus. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4566574/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

John Fitzgerald. 2009. The Greatest Movie Scene Ever? – Mega Shark vs. Giant Octopus!. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I16_8l0yS-g. Last accessed 08/05/2025

JohnBarrowman.com. SHARK ATTACK 3: MEGALODON. https://www.johnbarrowman.com/film/sharkattack.shtml. Last accessed 08/05/2025

IMDb d. Shark Attack 3: Megalodon. https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0313597/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

QI. 2025. “This Would Make A Great Drinking Game!” | QI. https://youtu.be/iVTzrMlITg4?si=GEcFmTCQzLCEHTgY. Last accessed 08/05/2025

Megalodon Collective. About. https://megalodoncollective.wordpress.com/about/. Last accessed 24/05/2025

Stavanger Jazzforum. Megalodon Collective. https://stavangerjazzforum.no/artister/megalodon-collective-2/. Last accessed 24/05/2025

IMDb e. Shark Tale. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0307453/. Last accessed 24/05/2025

IMDb f. Mako: The Jaws of Death. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0074845/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

FILMIX. 2024. Mako: The Jaws of Death (1976) | RETRO HORROR MOVIE | Richard Jaeckel – Jennifer Bishop – Buffy Dee. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZ0STRVwWaA. Last accessed 08/05/2025

IMDb g. Ti-Koyo e il suo pescecane. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0061096/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

G.E.G. GEG2. 2023. Ti-Koyo e il suo pescecane- Film completo 1962. https://youtu.be/3rbTGKiOx6g?si=bZiRhBf-ISUknr4E. Last accessed 08/05/2025

MUBI. TIKO AND THE SHARK. https://mubi.com/en/gb/films/tiko-and-the-shark. Last accessed 08/05/2025

La Stampa. 1962. La Stampa – Friday 23 November 1962. http://www.archiviolastampa.it/component/option,com_lastampa/task,search/mod,libera/action,viewer/Itemid,3/page,4/articleid,0089_01_1962_0265_0004_17401956/anews,true/. Last accessed 08/05/2025

Metacritic. Jaws Unleashed. https://www.metacritic.com/game/jaws-unleashed/. Last accessed 24/05/2025

Goodreads. Quint. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/181211787-quint. Last accessed 24/05/2025

Board game geek. Jaws (2019). https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/272738/jaws. Last accessed 24/05/2025

LMG Vids. 2025. Universal Studio Tour in the Rain – Universal Studios Hollywood – 2025 Rides POV | 4K 60FPS. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IqvjzHEy3VI. Last accessed 24/05/2025

Image sources

Ellie Sattler. 2023. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Megalodonte_a_caccia.jpg

Robert W. Boessenecker, Dana J. Ehret, Douglas J. Long, Morgan Churchill, Evan Martin, Sarah J. Boessenecker. 2019. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otodus_megalodon_from_Niguel_Fm.png

Emőke Dénes.2012. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hal_-_Megalodon_tooth.jpg

Mark P. Witton. 2018. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cretoxyrhina_attacking_Pteranodon.png

Jambura PL and Kriwet J. 2020. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ptychodus_vertebra.PNG

James St. John. 2008. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giant_white_shark_coprolite_(Miocene;_coastal_waters_of_South_Carolina,_USA).jpg

Hugo Saláis. 2016. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otodus_megalodon_in_sea_restoration.jpg

Crudmucosa. 2023. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Megalodon_reconstruction.jpg

Skvader. 2018. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dinosaur_Land_sign.jpg

PLBechly. 2024. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Megalodon_snacking.jpg

Fallows C, Gallagher AJ, Hammerschlag N. 2013. [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:White_shark_(Carcharodon_carcharias)_scavenging_on_whale_carcass_-_journal.pone.0060797.g004-B.png

Tore Sætre. 2016. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Megalodon_Collective_(214227).jpg

Andrew Thomas from Shrewsbury, UK. 2010. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jaws_(5530370622).jpg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution.