by Matthew Norton

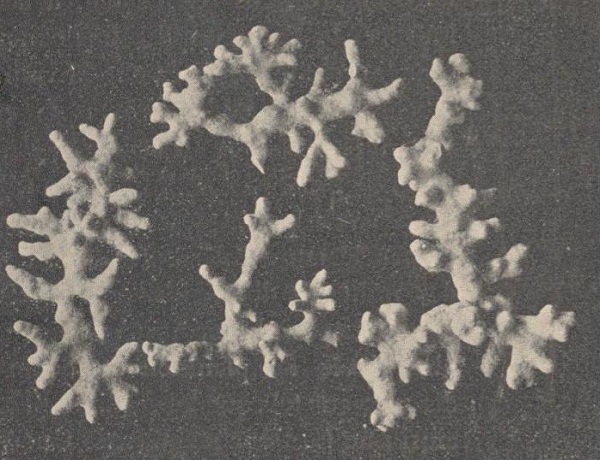

In the ocean, things are not always as they appear to be. For example, corals can easily be mistaken for some kind of hardened plant or seaweed, rather than the colony of polyps (tiny animals related to jellyfish and anemones) they actually are. And it’s easily done, given how each colony cements itself to one spot and gets most of its food from sunlight via photosynthesis, albeit through the microscopic algae (i.e. zooxanthellae) they keep. But there are times when nature pulls the old switcheroo and gives us an actual seaweed that looks like coral. Such is the case with the corraline red seaweeds commonly known as maerl.

There are a number of species that come referred to as maerl, including (but not limited to) Phymatolithon calcareum and Lithothamnion corallioide. Broadly speaking, they are pink-purple in colour and start out as unattached nodules (or crusts), each adorned with an outer layer of calcium carbonate, just like a coral’s exoskeleton, as they roll about like a tumbleweed. And assuming they survive this literally turbulent time, these nodules will eventually grow too heavy for the currents and waves to throw about, allowing them to settle and possibly form part of a maerl bed (such aggregations may also be called “rhodoliths”). Kind of like a dense, but not too dense carpet of living gravel on a typically soft sediment (varying from mud to coarse sand).

The exact density of a particular maerl bed can depend greatly on local conditions, such as thicker beds being the ones to survive and develop in areas exposed to stronger currents and/or wave action. While sheltered areas favour the thinner maerl beds that are more likely to play host with epiphytic algae (i.e. a seaweed that grows on another seaweed). It’s even been suggested that the shape, structure and surface features of constituent maerl nodules could be a handy indicator of what the water movements are like for a given stretch of coastline over a long period of time. Even the most dedicated researchers can’t take measurements continuously 24/7. It is worth mentioning however, that a bare minimum of water movement is required to keep silt from building and smothering the maerl bed.

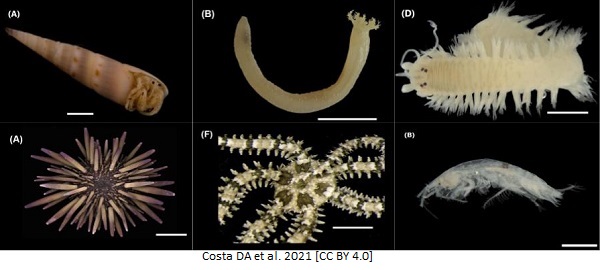

Assuming that conditions are adequate and the site remains unaffected by disaster or major disturbance, a maerl bed can grow into a highly complex 3D structure, with living maerl growing on the foundations of their dead, but still hard and chalky predecessors. And with the little and (often) difficult to reach spaces between their interlocking thalli (the parts of the nodules that look like twigs) the maerl effectively creates a living maze in which a whole assortment of sea creatures can live on or within. These include (but again, are not limited to) bivalve molluscs, worms, anemones, urchins, sea cucumbers, brittle stars and octopus.

Sometimes, these maerl bed residents will remain small and in need of these hiding places for their whole lives. Sometimes, they simply need a safe refuge during their early years, until they are big and strong enough to take on the big wide world. In the case of the latter, maerl has proven useful for some commercial species, such as queen scallops, soft clams and even gadoid fish like Atlantic cod, pollock and saithe. Maerl isn’t necessarily the only nursery habitat these species would rely on, but would you gamble away your fish fingers or tasty scallops (hopefully caught sustainably) just to find out?

But as effective as maerl is at providing these diverse habitats and eking out a living for itself, generating its food through photosynthesis and absorbing the necessary minerals from the surrounding water, it’s all achieved very slowly. Different sources quote different figures, but the growth rate usually averages out somewhere between 0.4-1mm per year. These growth increments are so small that it’s sometimes necessary to use high-tech solutions like scanning electron microscopes and Alizarin staining (commonly used to detect bone growth and calcium deposits) to measure them accurately. And even then, the result can fluctuate wildly depending on environmental factors, especially temperature and light levels, which themselves can fluctuate on a variety of timescales (e.g. seasonal vs. daily variations).

On the flip side, the slow growth of maerl is matched by a long lifespan, with individuals recorded to have lived over 100 years while whole beds have been dated back thousands of years. For example, there are maerl beds off the coast of Brittany, France that are thought to be around 5,500 years old. A testament to the slow and steady lifestyle to which they are very much committed, and which also enhances their status as a carbon sink. All that carbon that today’s maerl is incorporating into their calcium carbonate exoskeletons, and their soft tissue, could be prevented from re-entering the water (and the atmosphere) for a very long time.

Unfortunately, while the adaptations of maerl are effective against the challenges of the natural world, their resilience against human interventions is far from assured. It’s an issue that they’ve been dealing with for some time, with maerl being directly harvested for fertilisers and soil conditioners for centuries. Even Pliny the Elder (the Roman scholar, author and naturalist) observed Celtic people using ‘Marga’ to enrich their soils.

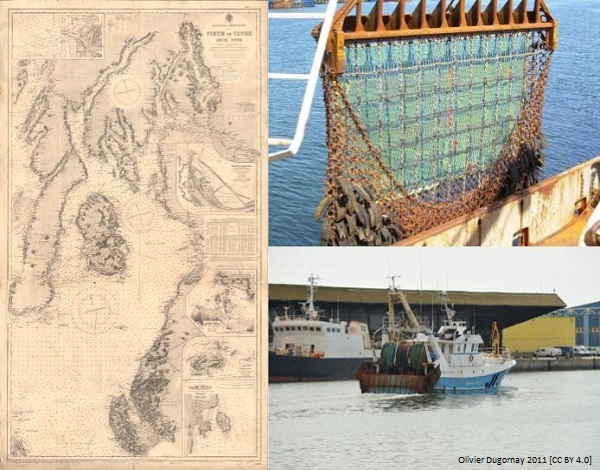

In more recent years, maerl has been used in the making of cosmetics (e.g. GELYOL® P.C. 25) for “stimulating skin vitality and energy” among other things, as well as a supplement in horse feeds to prevent gastric ulcers. But given their incredibly slow growth rate, the exploitation of maerl is far from sustainable, especially when it’s dredged up from the seafloor, leaving behind only a few smashed up pieces and a habitat that will remain damaged for a long time. Even the maerl beds not directly caught in a dredge’s path can be impacted by all the sediment (sand, mud, silt etc) thrown up by these kinds of fishing gear. Whether its suspended in the water, or blanketing the maerl, that sediment will obstruct much of the light attempting to pass through it. A big problem for seaweeds who need that light to photosynthesise.

Worse still, any organic material (e.g. faecal matter, bits of dead sea creature) dragged out of the sediment, and then decomposed by the relevant microorganisms, can bring down the local oxygen concentration. As can certain types of pollution, such as organic pollution from sewage pipes and fish farms as well as fertilisers from farms further inland, which runoff into rivers and then later into the sea. The latter causes a phenomenon called ‘eutrophication’, where the sudden upsurge of nutrients can drive an equally abrupt bloom of phytoplankton (microscopic algae). This would initially drive up the oxygen concentration as these phytoplankton photosynthesise, until much of the bloom dies, sinks and decomposes, sucking away that precious oxygen for habitats nearer the seafloor (such as maerl beds).

On a positive note, maerl is generally found all over the world, from the tropics to the polar regions and down to around 270m below the ocean surface (if the water above is clear enough), so there may very well be pristine beds that remain relatively untouched to this day. And as well as reproducing in the traditional sense, they can also (at least to a moderate extent) reproduce via fragmentation, with each snapped off piece having a chance at growing and beginning anew.

But these advantages have their limits, including the limited distributions of certain species of maerl, our aggressive tendencies towards seeking out new resources wherever we can get them, and the global effects of climate change and plastic pollution, which has proven to permeate into areas that few humans have seen with their own eyes. The ocean, and nature as a whole, has the capacity to withstand the damage we inflict upon its habitats and ecosystems to an extent, But it can’t hold out forever.

From a human perspective

“Ocean: With David Attenborough” hit cinemas earlier this year, drawing attention to the beautiful wonders of the undersea world and how threatened they are from the raw and reckless destruction of unsustainable fishing practices. The bottom trawling scene (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzG9AwlypaY) was particularly disturbing, like something out of a brutal disaster film.

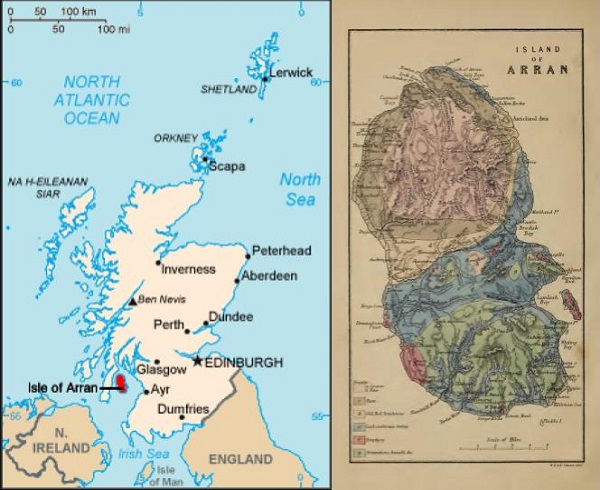

But there was also hope in those 95 minutes of screen time, proof that the ocean can recover if we give a chance to do so. Marine protected areas (MPAs), spaces where fishing and other potentially damaging activities are restricted, were regularly cited as a particularly effective tool for managing our seas. As evidenced by a number of case studies and guest narrators, including Don MacNeish, co-founder of the Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST), a charity that played a key role in establishing the MPA that covers the south side of Isle of the Arran in Scotland.

The South Arran MPA forms a kind of semicircle around (as the name suggests) the southern of the island from (approximately) King’s Caves on the western side, all the way to Corriegills on the eastern shore.

Check out https://www.arrancoast.com/south-arran-mpa/ for a more detailed representation.

What does this have to do with maerl you may ask? Well, before the South Arran MPA (designated in 2014; legally enforced from 2016), there was the Lamlash Bay No Take Zone (NTZ). Established in 2008 and covering an area of 2.67km², it offers the highest form of protection where (as the name suggests) no sea life can be taken by any method. It also contains one of the largest maerl beds in Scotland, providing a critical habitat for dogfish, king scallops, queen scallops, crabs, starfish, flatfish, sea squirts, brittle stars and so on. The logo for COAST even features a piece of maerl (https://www.arrancoast.com/), demonstrating its continued importance in their efforts to protect and celebrate the island’s waters.

Butt hasn’t always been smooth sailing for COAST. Originally formed by Don MacNeish and Howard Wood OBE in 1995, it was a long and hard fought campaign to get that NTZ. The determination was there however, borne from their firsthand experience of diving around Arran and witnessing the deterioration of their local seas. Particularly from the damage inflicted by mobile fishing gear like trawls and scallop dredges, along with the dwindling abundance of plaice, sole, rays and other fish that were once abundant on the seafloor. Worse still, the Lamlash Sea Angling festival, once a renowned annual event, was ultimately cancelled in 1994 due to the abysmal lack of fish. Clearly, something had to be done.

Alas, the concerns of two well informed divers are unlikely to convince a government, or any other legal body, to take effective action (no matter how often we wish this was the case). Howard and Don needed support and lots of it, so they adopted a bottom-up approach to their campaign, using those early years to engage with local groups and residents on the island. To make their case they used (among other things) old fishing photos to demonstrate the bountiful catches that anglers could achieve 10-15 earlier, as well as their own photos of the seabed to prove what was left to protect. This all led to the critical step of gathering all the local Arran fishermen at a pub in 1998 to finalise the exact location of their proposed NTZ.

From this strong, grassroots foundation, COAST was able to go forth and correspond with the relevant government agencies and gradually build up political support from further afield. A daunting task for sure, but the idea was not entirely without precedent. A few years before COAST was officially founded, Don travelled to New Zealand and met Dr. Bill Ballantine (1937-2015), who tirelessly campaigned for a series of marine reserves within the nation’s waters. Ultimately, he played a key role in developing the Marine Reserves Act 1971, which created 44 such reserves (all of them NTZs). Needless to say, Dr. Ballantine’s efforts had a profound effect on both Howard and Don, but the gruelling 12 years of bureaucracy clearly shows what one can expect from such campaigns. The man himself once compared the process to being a drunk trying to open a locked door: “You have to be at the right door, and be holding the right key, but beyond that it’s just persistence.”

This was certainly the case for Howard, Don and everyone else involved with COAST in its early years. The political will from Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) was somewhat lacking at the time (particularly after the disastrous Loch Sween MPA proposal) and the influence of large scale fisheries from further afield posed a significant challenge. Some, like the Southwest Static Gear Association (CSSGA), who represent static gear fishermen (e.g. those who use creel pots) were all for the NTZ. But the Clyde Fishermen’s Association (CFA), who represented mobile gear fishermen (e.g. trawlers and dredgers) were opposed to the idea. They would sometimes argue that local communities were (at best) minority stakeholders when it came to the sea and would ‘drag their heels’ during many of the discussions held with COAST.

But their failure to properly consult local stakeholders early in the planning stage, along with lack of compensation for the income that would be lost, led to a strong pushback. The benefits of the MPA for tourism and sustainable fishing were said to be explained in a broad sense, but the aforementioned lack of consultation had already doomed the proposal.

In 2014, the loch was designated as a Nature Conservation MPA, but the first attempt stands as a perfect example of how not to do it.

The people of the CFA may have had the livelihoods to consider, it should be noted that the Firth of Clyde (not just the waters around the Isle of Arran) was in dire state. The commercial fish stocks, from species such as cod, haddock and hake, had been declining from the 1980s-early 1990s, with significant landings of whitefish in general ceasing after 2003. With herring stocks (which had sustained communities in the area since the 15th century) not doing much better, many fisheries resorted to trawling for Nephrops prawns (the kind that go into making scampi).

While the signs of serious declines were noted from the 1980s, it seems the exact opposite of responsible action was taken at the time, with a previous ban on trawling within three nautical miles of the shore being lifted in 1984. Fortunately, more recent efforts have been put in place to at least give the Firth of Clyde a fighting chance of thriving again, such as the eventual banning of Scallop dredgers (top right) and trawlers (bottom right) in 2022 and a closure of cod fishing during the spawning season in 2024, and then again in 2025.

Naturally, there were going to be critics of such measures, especially among local fishing communities. But the Firth of Clyde is often regarded as one of the most heavily impacted marine environments by human action in the world, with some dramatically suggesting the area had undergone an “Ecological Meltdown”. What else but dramatic (if painful) measures could hope to bring it all back?

Despite all the hurdles, COAST continued campaigning for the NTZ, engaging with policy makers, building up their memberships, strengthening the proposal with rewrite after rewrite and recording all the habitats and sea creatures that were there to be found in Lamlash Bay. The latter provided particularly useful evidence during a 2004 campaign against plans by Scottish Water to install a sewage pipe that would discharge its effluent straight into Lamlash Bay, and into the path of maerl beds that COAST were trying to protect. The eventual decision to reroute the pipe was the organisation’s first big win, and from there they kept going, and going, and going until the Lamlash Bay NTZ was finally established in 2008.

Check out https://www.arrancoast.com/no-take-zone/ for a more accurate representation.

That was a very, very brief summary of the events that led to the Lamlash Bay NTZ, but there is a full, detailed account on the official COAST website: The Lamlash Bay No-Take Zone: A Community Designation. Be warned though, it is a long read which perfectly reflects the long and frustrating process they went through (as previously mentioned). But from there COAST really did go from strength to strength, with the introduction of the wider South Arran MPA and then, in the summer of 2018, the opening of the COAST Discovery Centre in Lamlash. Which (without blowing my horn too much) is where I came in.

It was the first volunteering opportunity I’d landed since finishing university the previous year (and working in a warehouse so that I actually had some money in my bank account), my first chance to gain some real world experience in marine conservation. Even before the centre was fully opened to the public, there was plenty to do, from generating website content about the sea creatures around Arran to helping set up the mobile aquarium tank that would become the centrepiece of the small, but effective exhibition space. All while facilitating the building’s previous function as an outside tennis court, co-organising an fundraising art exhibition and rockpooling with visiting school groups. But naturally, things got more lively once the centre was open and the summer holidays were in full swing, with regular day-to-day interactions with visitors. These kinds of engagement are undoubtedly important, not just for the sake of doubling down on the community focus that underpinned COAST’s prior successes, but also for securing the future of Arran’s seas. The NTZ and MPA were firmly established, but that didn’t mean the job was done.

There are certainly worse places to spend four months volunteering.

One of the biggest issues during my time with COAST was a proposed salmon farm near Lochranza on the north side of the island, a proposal submitted by the Scottish Salmon Company (SCC; now named “Bakkafrost Scotland” after the Faroe Islands based company that acquired them in September 2019). Generally, fish farming is lauded by some for its potential economic benefits and the idea that it might reduce the pressure of wild populations of commercial fish species. Alas, the practice comes with a number of environmental concerns, with fish farms (especially those which are poorly managed) potentially being :

- A source of organic pollution, in the form of faceal matter and uneaten food, which may decompose and suck away the oxygen from the surrounding waters (as mentioned earlier in this article).

- A breeding ground for parasites (e.g. sea lice) and pathogens (i.e. disease causing microbes) which can spread beyond the confines of the fish pens. The medicines used to combat them can also leach out beyond the farm and cause collateral damage among the wild sea life.

- A source of disturbance via the acoustic devices that may be used to keep away large predators like dolphins and seals.

Combine all of the above with the prospect of spoiling a beautiful natural landscape, which one can easily find on the Isle of Arran, and the push for an intensive salmon farm was hardly going to be popular. As evidenced by an exit poll that COAST organised in April 2019, following public talks with the SCC, which revealed 89% were opposed to the farm while 10% were undecided and 1% were in favour. And it didn’t take long for the subsequent petition against the farm to accumulate signatures from the majority of the island’s permanent residents, followed by protest banners and a human chain demonstration later that year. You can’t get a much clearer answer than that.

But let us not forget that you also need evidence to show that NTZs and MPAs actually work, otherwise what would you have engage with? As previously mentioned, Howard and Don already had the local knowledge and experience during COAST’s early years, but strong scientific evidence required the use of rigorous survey techniques and the accurate identification of species on the seabed. Fortunately, the Marine Conservation Society (MCS) were happy and willing to provide the necessary Seasearch training for local divers. The subsequent data they collected proved to be a major asset in the aforementioned 2004 campaign against the sewage pipe in Lamlash Bay. In more recent years, the monitoring work has continued, with COAST even acquiring their own vessel in 2022 for research and outreach purposes.

As a result, the recovery of Arran’s waters since the protected areas were established is well documented, and has received a lot of attention from the media and scientific literature. Within the NTZ specifically, there’s been a general increase in biodiversity, with greater densities of maerl, hydroids, sponges, feather stars and macroalgae (i.e. seaweeds other than maerl) compared to nearby areas of seabed. A pattern that also applies to the abundance of commercial species like king scallops and European lobsters, which can then spill over into areas where they can be caught legally and (hopefully) sustainably. It really is a testament to the efforts of COAST and their supporters, as well as providing a valuable case study to show that MPAs can work when they are done right.

It’s the kind of optimism we really do need right now. But not at the expense of getting complacent when we actually succeed in our efforts to protect the natural world. Instead, we must remain constantly on our guard against the likely pushback from the misinformed, those who have vested interests in weakening these kinds of protective measures, and those who are somewhere in between. In the case of COAST, it’s easy to see how someone could frame the organisation as being anti-fishing altogether (despite the support from many local and static gear fisheries), and then stir up a wave of hostility based on that misconception. Sadly, it seems to be the way that many arguments are made these days, to attack one group of people based on the false (or greatly exaggerated) impression that you’re protecting another group of people. But Don made the truth about his intentions very clear during his contribution to “Ocean: With David Attenborough”: “I’m not saying that people shouldn’t catch fish, eat fish, and fishermen shouldn’t be able to make a living. But they shouldn’t be able to do it in a way that is just breaking everything.”

Sources

NatureScot. 2023. Maerl beds. https://www.nature.scot/landscapes-and-habitats/habitat-types/coast-and-seas/marine-habitats/maerl-beds. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Perry et al. 2024. Maerl beds. https://www.marlin.ac.uk/habitats/detail/255/maerl_beds. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Scottish Wildlife Trust. Maerl Phymatolithon calcareum. https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/species/maerl/. Last accessed 04/07/2025

Jardim et al. 2022. Quantifying maerl (rhodolith) habitat complexity along an environmental gradient at regional scale in the Northeast Atlantic

Bosellini and Ginsburg. 1971. Form and internal structure of recent algal nodules (rhodolites) from Bermuda

NatureScot. 2016. 2016 Mousa maerl bed octopus. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enK29eQ2p90. Last accessed 04/07/2025

Costa et al. 2021. Marine invertebrates associated with rhodoliths/maërl beds from northeast Brazil (State of Paraíba)

Kamenos et al. 2004. Nursery-area function of maerl grounds for juvenile queen scallops Aequipecten opercularis and other invertebrates

Kamenos et al. 2004. MAERL: ITS VALUE AS A NURSERY HABITAT FOR COMMERCIAL SPECIES

Kamenos et al. 2004. Small-scale distribution of juvenile gadoids in shallow inshore waters; what role does maerl play?

Blake and Maggs. 2003. Comparative growth rates and internal banding periodicity of maerl species (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) from northern Europe

Grall and Hall-Spencer. 2003. Problems facing maerl conservation in Brittany

O’Reilly et al. 2012. Chemical and physical features of living and non-living maerl rhodoliths

Sordo et al. 2020. Seasonal photosynthesis, respiration, and calcification of a temperate maërl bed in southern Portugal

Wilson et al. 2004. Environmental tolerances of free-living coralline algae (maerl): implications for European marine conservation

Stannard. 2025. Pliny the Elder. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pliny-the-Elder. Last accessed 06/09/2025

CliniSciences. Alizarin red stain. https://www.clinisciences.com/en/buy/cat-alizarin-red-stain-5402.html. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Twose. 2023. Competing with gastric ulcers: What you need to know. https://www.spillers-feeds.com/competing-your-horse-with-gastric-ulcers?srsltid=AfmBOopxsptbY5y69Ut2RKA5iaGxlSzjYJbw8eLO5_J10DX59aMsV7ng. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Ultrus Prospector. GELYOL® P.C. 25. https://www.ulprospector.com/en/eu/PersonalCare/Detail/15394/1020726/GELYOL-PC-25. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Allen & Page. Soothe & Gain: A High Calorie Conditioning Feed. https://www.allenandpage.com/product/soothe-gain/. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Bernard et al. 2019. Declining maerl vitality and habitat complexity across a dredging gradient: Insights from in situ sediment profile imagery (SPI)

Divernet. 2016. MMO ignores Cornwall dredge campaigners. https://divernet.com/scuba-diving/mmo-ignores-cornwall-dredge-campaigners/. Last accessed 27/08/2025

Pezij et al. 2024. Health status and characterisation of Gibraltar’s maerl beds

Hall-Spencer et al. 2006. Impact of fish farms on maerl beds in strongly tidal areas

Grall and Hall-Spencer. 2025. Maerl Bed Conservation: Successes and Failures

IMDb. 2025. Ocean with David Attenborough. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt33022710/. Last accessed 20/07/2025

Altitude Films. 2025. OCEAN WITH DAVID ATTENBOROUGH | BOTTOM TRAWLING OFFICIAL CLIP | IN CINEMAS NOW | Altitude Films. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzG9AwlypaY. Last accessed 01/08/2025

Community of Arran Seabed Trust. South Arran MPA. https://www.arrancoast.com/south-arran-mpa/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Community of Arran Seabed Trust. No Take Zone. https://www.arrancoast.com/no-take-zone/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Community of Arran Seabed Trust. The Lamlash Bay No-Take Zone

A Community Designation. https://ffi.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=70448e12ec3c45139beca33dfc990b7a. Last accessed 21/09/2025

Department of Conservation: Te Papa Atawhai. 2015. Remembering New Zealand’s ‘father of marine conservation’. https://blog.doc.govt.nz/2015/12/14/remembering-bill-ballantine/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Department of Conservation: Te Papa Atawhai. Marine reserves A to Z. https://www.doc.govt.nz/marinereserves. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Goldman Environmental Foundation. 2016. Remembering Marine Conservation Hero, Bill Ballantine. https://www.goldmanprize.org/blog/remembering-marine-conservation-hero-bill-ballantine/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Spirit of the Highlands and Islands. Loch Sween. https://discoverhighlandsandislands.scot/en/visitor/location/loch-sween. Last accessed 01/08/2025

British Sea Fishing. The Decline of the Firth of Clyde. https://britishseafishing.co.uk/the-decline-of-the-firth-of-clyde/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Scottish Government. 2021. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Volume 3 Number 3: Clyde Ecosystem Review. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-marine-freshwater-science-volume-3-number-3-clyde-ecosystem/pages/6/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Richardson. 2021. Clyde’s fish stocks start to recover – with a different fish than before. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/07/clydes-fish-stocks-start-to-recover-with-a-different-fish-than-before. Last accessed 06/09/2025

McBride. 2024. Firth of Clyde Cod Closure to Remain in Place for 2025 States Gougeon. https://thefishingdaily.com/latest-news/firth-of-clyde-cod-closure-to-remain-in-place-for-2025-states-gougeon/. Last accessed 06/09/2025

Thurstan and Roberts. 2010. Ecological meltdown in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland: two centuries of change in a coastal marine ecosystem

Jones. 1999. Marine nature reserves in Britain: past lessons, current status and future issues

Fraser 2019. Scottish Salmon Company bought by Faroese fish farm. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-49833904. Last accessed 21/09/2025

Bakkafrost. The Scottish Salmon Company renames operations in Scotland. https://www.bakkafrostscotland.com/news/the-scottish-salmon-company-renames-operations-in-scotland. Last accessed 21/09/2025

McEachern. 2019. Proposed salmon farm off Arran met with fury by locals and environmentalists as industry comes under increasing criticism. https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/proposed-salmon-farm-on-arran-met-with-fury-by-locals-and-environmentalists-as-industry-comes-under-increasing-criticism/. Last accessed 21/09/2025

Carrell. 2019. Protests at plans for salmon farm near Lochranza, on Arran. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/dec/31/protest-plans-salmon-farm-lochranza-arran. Last accessed 21/09/2025

COAST. 2022. The start of an exciting new era for COAST. https://mailchi.mp/arrancoast/protect-scotlands-seas-from-damaging-discarding-coast-summer-news-9766609?e=[UNIQID]. Last accessed 01/08/2025

COAST. COAST in the media. https://www.arrancoast.com/coast-in-the-media/. Last accessed 21/09/2025

Stewart et al. 2020. Marine conservation begins at home: how a local community and protection of a small bay sent waves of change around the UK and beyond

Howarth et al. 2015. Sessile and mobile components of a benthic ecosystem display mixed trends within a temperate marine reserve

Image sources

ArranCOAST. 2004. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ARRAN_SEASCENES_013.jpg

Saryu Mae. 2022. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corallina_officinalis_at_Kakamatua_Point,_Huia.jpg

Frithjof C. Küpper. 2013. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coralline_algae_2.jpg

FalsePerc. 2006. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coralline.1.jpg

Olivier Dugornay. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Banc_de_ma%C3%ABrl_en_rade_de_Brest_(Ifremer_00686-79814_-_32446).jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pagurus_criniticornis_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_10_a.jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chiridota_rotifera_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_11_b.jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceratonereis_singularis_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_4_d.jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Echinometra_lucunter_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_11_a.jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ophiactis_savignyi_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_11_f.jpg

Costa DA, Dolbeth M, Prata J, da Silva FA, da Silva GMB, de Freitas PRS, Christoffersen ML, de Lima SFB, Massei K, de Lucena RFP. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elasmopus_brasiliensis_(10.3897-BDJ.9.e62736)_Figure_9_b.jpg

Olivier Dugornay. 2001. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Araign%C3%A9e_m%C3%A2le_sur_fond_de_ma%C3%ABrl_(Ifremer_00557-66908_-_20311).jpg

Olivier Dugornay. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Petite_roussette_sur_fond_de_ma%C3%ABrl_(Ifremer_00686-79812_-_32436).jpg

Colin. 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Close-up,_Coral_beach,_Isle_of_Skye.jpg

Emkaer. 2008. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coral_Fragments,_Coral_Beach,_Carraroe.JPG

Erik del Toro Streb. 2020. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieces_of_maerl_from_Majanicho_(Fuerteventura_island)_on_human_hand.jpg

ArranCOAST. 2003. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COAST_logo.jpg

L J Cunningham / Clauchlands Farmland, Lamlash, Arran. 2006. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clauchlands_Farmland,_Lamlash,_Arran_-_geograph.org.uk_-_185770.jpg

Richard Webb. 2023. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boat_leaving_Loch_Sween_-_geograph.org.uk_-_7636095.jpg

Olivier Dugornay (IFREMER, Pôle Images, Centre Bretagne – ZI de la Pointe du Diable – CS 10070 – 29280 Plouzané, France). 2011. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chalutier_Le_Pr%C3%A9curseur_retournant_au_port_de_Boulogne-sur-Mer_(Ifremer_00760-87155_-_45848).jpg

John Allan. 2011. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salmon_farm_cages_below_Toravaig_-_geograph.org.uk_-_2567640.jpg

All other images are public domain, or my own photos, and do not require attribution.