by Matthew Norton

What is the difference between an animal and a plant? What is different about how one interacts with the world around them compared to the other? Perhaps the most obvious answer is that plants tend to exist and grow from one spot whereas animals are noticeably more mobile. On land, this appears to be a fairly clear cut boundary between plant and animal life, but in the ocean the line is more blurred. There are seaweeds that exist as floating masses and multitudes of different animal species who cement themselves to one spot for almost their entire lives. The latter lifestyle is only possible because they are effectively living in a whirling soup of microscopic plankton and other associated morsels. Why waste the energy when you can simply wait for your dinner to come to you?

It’s a strategy that, while undoubtedly efficient, can quickly falter if the local food supply dries up, or a persistent predator approaches, or the local habitat becomes uninhabitable. Assuming the individual animal had the chance to spawn and spread out their young, then its untimely death may be inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. Still, it would be nice to have an escape strategy, no matter how temporary. This is where feather stars come in, with plant-like arms that they can stretch out and filter food from the passing water, but who can also relocate themselves if the need arises. Perhaps feeling a little smug in the process, if they are capable of feeling this kind of emotion.

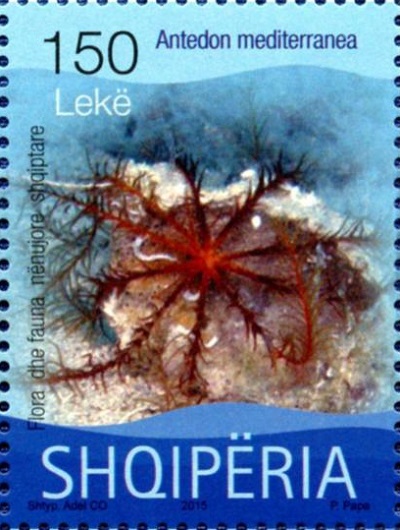

Feather stars, also known as crinoids, are part of the echinoderm phylum, a group that also includes starfish, sea urchins and sea cucumbers. But while their cousins tend to use rows upon rows of sticky ‘tube feet’ to keep them attached to the seabed, feather stars are usually found anchored on harder surfaces (e.g. rock, corals) using hook-like structures called cirri on the base of their body. These hooks can be engaged and then disengaged at will to allow the feather stars to either crawl about, or even swim (depending on the species) to find a new home. A swimming feather star can make for some strangely hypnotic viewing.

For the sake of clarity, it is worth mentioning that there is another group of crinoids that are commonly referred to as ‘sea lilies’. These creatures are usually stalked and immovable throughout their lives whereas feather stars generally possess these stalks during their younger years before ultimately ditching them. I say ‘usually’ and ‘generally’ because some sea lily species also possess detachable cirri and this whole thing about how the stalks separate the two groups of crinoids has a rather messy history in the fossil record. Alas, nature rarely conforms to the strict groupings we try to assign to it.

But if we look a little closer, we find that even when the body is fixed in one place, temporarily or permanently, there are still things to do and movements to make. For example, each arm of a feather star is adorned with side branches called pinnules which contain multitudes of tube feet that sieve out the microscopic morsels of food and flick them towards a central feeding groove. These grooves are filled with tiny, hair-like cilia that shuffle the food towards the mouth and perform any necessary sorting between the edible and non-edible pieces. It’s like there are hundreds of little workers working a single conveyor belt.

The workload required to keep themselves fed can also pose quite the conundrum to a feather star, should they detect a potential predator. Flinch too soon and they could lose valuable feeding time and a prime location by flying away from what might prove to be a false alarm. Even if the threat is confirmed, a tactical retreat won’t necessarily be the first defence they might call upon. Feather stars can avoid the notice of predators through camouflage and particular feeding habits (there is some evidence to suggest they feed more at night to avoid predators). They may also deter predators with thick, densely branched arms, thick and spiky pinnules and/or the use of chemicals that give them an unpleasant taste. And should a predator overcome all of this and attack before the feather star can escape, they are able to regenerate certain parts of their body and survive otherwise fatal wounds. Even the loss of their digestive system can be tolerated by directly absorbing nutrients from the water as a temporary measure.

In conclusion, there seems to be numerous advantages to the flexible lifestyle of a feather star. Compared to their stalked sea lily cousins, they have more species alive today (550 v.s. 80) and can be found in shallow waters and the deep sea whereas sea lilies appear restricted to the latter, with the shallowest species living 100m below the surface. This may simply be because feather stars have more control over their destiny throughout their lives, whereas most benthic species can only disperse across meaningful distances as very young larvae. Some play it safe and stick to areas that are already flooding with their own kind while others venture out to new grounds, risking it all with little chance of success. But feather stars can adopt both strategies, they can be both prudent and pioneer with the ability to change their mind at a moment’s notice.

From a human perspective

Like many sea creatures, crinoids have found themselves thrust into various corners of human history and culture. For example, the fossilised remains of sea lily stalks can be found, preserved in the rock but broken down into little segments, like star shaped polo mints. They have been described as fairy coins, star stones and St. Cuthbert’s beads, in reference to a seventh century priest who reportedly held them as part of a rosary.

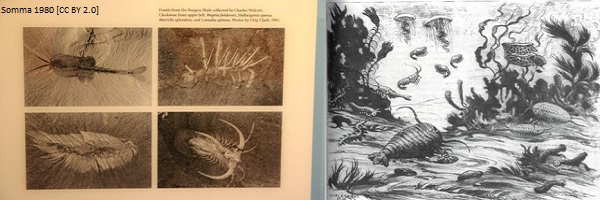

These images do not follow the same set of fossil fragments.

But these remains also hold clues to a time long before our species evolved into being, with sea lily fossils being found within the rocks of modern day seasides and in rocks that are now far away from the ocean. The latter indicates that a now terrestrial (i.e. dry land) environment was once underwater, possibly hundreds of millions of years ago.

One of the most famous examples is the Burgess Shale, a site located high in the Canadian Rockies but which is full of fossilised sea creatures. And among these finds are the remains of soft bodied animals, which makes these shale rocks especially valuable since it’s usually only the hard parts, such as bones and shells, that survive the fossilisation process.

You need especially good fortune to find those rare soft bodied fossils, since these are the parts that will decompose first. This makes the Burgess Shale (left) such a renowned treasure trove of information about earth’s history. But if you’re very, very lucky, though I doubt the original creature who snuffed it would agree, you may also come across a creature perfectly preserved in amber (right).

Crinoid fossils are particularly useful fossils to find, for various reasons. Their presence alone can all but confirm that the area was a saltwater environment at that particular time in earth’s history, simply because echinoderms are incapable of surviving in freshwater. A quality not shared by other animal groups (e.g. vertebrates, molluscs, annelid worms) who have seawater and freshwater species among their ranks. Also, the fact that they are still alive today means we can use modern day crinoids as proxies (i.e. guides) for understanding how their ancestors might have lived. Combined with other parts of the puzzle we can glean from other fossils and preserved materials, we can at least begin to deduce how the entire prehistoric ecosystem might have functioned. But as well founded as the conclusions of one researcher, or more likely one research group, may be, they are almost always open to debate and interpretation. You could argue that palaeontology (the study of fossils) itself is mostly educated guesswork based on the sparse information at our disposal.

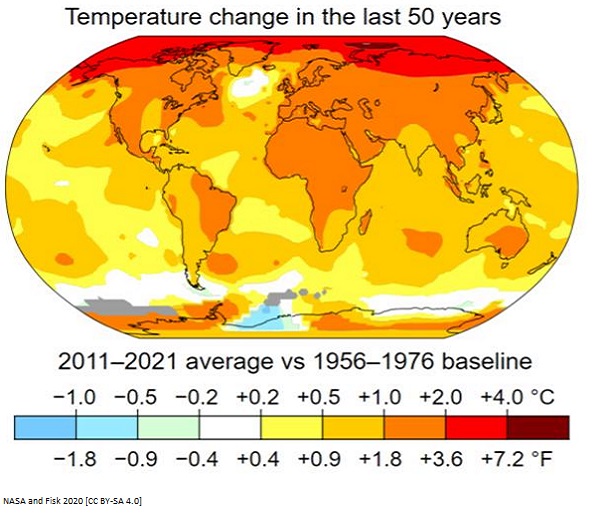

So why do we go to all this trouble? Scientific curiosity aside, there is a lot we can learn from species and whole communities that came and went millions of years ago. Particularly the warning signs of catastrophes like mass extinctions, which can be traced and dated through (relatively) sudden disappearances of whole animal groups in the fossil record. Assuming we can also measure the environmental conditions from around the times of these sudden disappearances, which we can do in a roundabout way, then we can begin to understand the triggers behind them. Of the five mass extinctions throughout the earth’s history (that we know of) the data suggests that rapid changes in global temperature and the levels of certain gases, like oxygen and carbon dioxide, were heavily involved in at least some of them.

Another climate indicator that we can glean from ice cores is the percentage of heavy oxygen (¹⁸O) to light oxygen (¹⁶O). Both versions are found in water vapour as it travels up from the tropics, but water molecules containing heavy oxygen are harder to evaporate into warm air and drop out more readily as rain as it reaches cooler air. The colder the earth as a whole is, the less heavy oxygen (relative to light oxygen) will reach the freezing cold Arctic and Antarctic to then be ensnared in future ice cores.

Should we have access to enough of these samples (top right), then we can really start to build a picture of how the global atmosphere has changed as demonstrated by data from the Vostok region in Antarctica (bottom). Note that each displayed interval for the age of the ice is 50,000 years (same as 0.5×10⁵ years).

If you’re thinking this all sounds familiar, it’s because our planet is currently going through a period of rapid climate change, due to the increased levels of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, that we are churning out into the atmosphere. In 2023, it might sound somewhat redundant to state this out loud, but there are those who still deny that climate change is happening, or that’s a major problem, or that it’s being caused by our burning of fossil fuels (among other unsustainable practices). It’s tempting to dismiss these people as idiots, or suggest that they have a vested interest in ignoring the overwhelming scientific consensus. But while this might be true for a select few individuals, other ‘climate sceptics’ may have misinterpreted the facts or been misinformed about the issue, leading them to reach conclusions that, while extremely flawed, do have some logic behind them.

A point that climate skpetics sometimes make is that climate change is simply a normal part of the earth’s cycle. This is true, even going back several hundred thousand years, there have been natural fluctuations in global temperature and the concentration of greenhous gases. But where this argument falters is with the speed at which these changes are happening today compared with back then. One study, published in 2017, estimated that human activities are heating up the Earth around 170 times faster than natural warming alone. While the exact figure might be debated, most would agree that human-induced climate change is fast outpacing anything that came before. This is especially worrying when you consider that a mass extinction event, by definition, occurs when species are going extinct faster than replacements can be found to fill the holes they leave behind in the natural world. And at this rate, the sixth mass extinction we seem to be heading for could be the most challenging yet for life on this planet.

But let us try and put all the doom and gloom to one side for a moment and end on a positive note (nothing will ever get done otherwise). It is important that we recognise the effect that we, as a species, are having on this planet and the kind of world we’re heading for if we don’t change our ways. But therein lies a slither of hope. We can change, it’s in our power to avert disaster. Just think of everything that humanity has achieved in the last 100 years, things that were once thought of as impossible to achieve and insane to dream of. We invented the internet, travelled out into space and developed cures for otherwise fatal diseases. We may be the cause of everything that threatens the natural world today, but if we can find a way to work with nature then we can make ourselves a critical part of the solution.

Sources

NOAA. What is Sargassum?. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/facts/sargassum.html. Last accessed 28/04/2023

Wikipedia. 2023. Crinoid. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crinoid#. Last accessed 01/04/2023

Rafferty. 2008. feather star. https://www.britannica.com/animal/feather-star. Last accessed 29/04/2023

Rodriguez et al. 2016. sea lily. https://www.britannica.com/animal/sea-lily. Last accessed 29/04/2023

Messing. 2017. Crinoids: Deep-sea Lily-like Animals. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/okeanos/explorations/ex1711/logs/dec7/welcome.html. Last accessed 28/04/2023

Mladenov and Chia. 1983. Development, settling behaviour, metamorphosis and pentacrinoid feeding and growth of the feather star Florometra serratissima

Stevenson et al. 2017. Predation on feather stars by regular echinoids as evidenced by laboratory and field observations and its paleobiological implications

Macurda and Meyer. 1974. Feeding posture of modern stalked crinoids

Meyer. 1973. Feeding behavior and ecology of shallow-water unstalked crinoids (Echinodermata) in the Caribbean Sea

Macurda and Meyer. 1983. Sea lilies and feather stars

Holland et al. 1986. Particle interception, transport and rejection by the feather star Oligometra serripinna (Echinodermata: Crinoidea), studied by frame analysis of videotapes

Birenheide and Motokawa. 1996. Contractile connective tissue in crinoids

Mladenov. 1983. Rate of arm regeneration and potential causes of arm loss in the feather star Florometra serratissima (Echinodermata: Crinoidea)

Smith et al. 1981. Amino acid uptake by the comatulid crinoid Cenometra bella (Echinodermata) following evisceration

Warner and Woodley. 1975. Suspension-feeding in the brittle-star Ophiothrix fragilis

Meyer and Macurda Jr. 1977. Adaptive radiation of the comatulid crinoids

Baumiller and Gahn. 2003. Predation on crinoids

Charmouth Heritage Coast Centre. Crinoids. https://charmouth.org/chcc/crinoids/. Last accessed 11/04/2023

British Geological Survey. Crinoids. https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/fossils-and-geological-time/crinoids/. Last accessed 11/04/2023

Lotzof. Snakestones: the myth, magic and science of ammonites. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/snakestones-ammonites-myth-magic-science.html. Last accessed 31/05/2023

Foster. 2021. You can find ‘fairy coin’ fossils in the UK for a free day out with the kids. https://www.dailystar.co.uk/travel/travel-news/you-can-find-fairy-coin-24802936. Last accessed 31/05/2023

Goodman. Crinoid Star fossil – 30 pieces – fairy coins – Great gift for collectors. https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/1120840107/crinoid-star-fossil-30-pieces-fairy. Last accessed 31/05/2023

Morris and Whittington. 1979. The animals of the Burgess Shale

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. The Burgess Shale. https://naturalhistory.si.edu/research/paleobiology/collections-overview/burgess-shale. Last accessed 01/06/2023

Butterfield. 1990. Organic preservation of non-mineralizing organisms and the taphonomy of the Burgess Shale

University of Kansas. Crinoids. https://geokansas.ku.edu/crinoids. Last accessed 01/06/2023

Boeuf. 2011. Marine biodiversity characteristics

Donovan. 2020. Train crash crinoids revisited

Berardelli and Niemczyk. 2021. The Great Dying: Earth’s largest-ever mass extinction is a warning for humanity. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/great-dying-permian-triassic-extinction-event-warning-humanity/. Last accessed 12/06/2023

Bauska. 2022. Ice cores and climate change. https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/our-data/publication/ice-cores-and-climate-change/. Last accessed 12/06/2023

Alley et al. The Vostok Ice Core. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth104/node/1267. Last accessed 23/06/2023

Riebeek. 2005. Paleoclimatology: the Oxygen Balance. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Paleoclimatology_OxygenBalance. Last accessed 23/06/2023

Begum. 2023. What is mass extinction and are we facing a sixth one? https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-mass-extinction-and-are-we-facing-a-sixth-one.html. Last accessed 12/06/2023

Earthday.org. 2021. 6 ARGUMENTS TO REFUTE YOUR CLIMATE-DENYING RELATIVES THIS HOLIDAY. https://www.earthday.org/6-arguments-to-refute-your-climate-denying-relatives/. Last accessed 13/06/2023

Gaffney and Steffen. 2017. The anthropocene equation

Image sources

Jay Nadeau, Chris Lindensmith, Jody W. Deming, Vicente I. Fernandez, Roman Stocker, David Liittschwager. 2006. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marine_microplankton.jpg

Philippe Guillaume. 2009. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trampa_mortal.jpg

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2010. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NOAA_stalked_crinoid.jpg

William I. Ausich. 1998. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crinoid_anatomy.png

Preview_H. 2007. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Feather_Star_1.jpg

Charles G. Messing. 1987. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ambulacrum_Crinoidea.png

Ria Tan from singapore. 2012. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Podia_of_a_red_feather_star.jpg

James St. John. 2017. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crinoid_stem_in_fossiliferous_limestone_(Lower_Mercer_Limestone,_Middle_Pennsylvanian;_Rt._16_roadcut_near_Trinway,_Ohio,_USA)_6_(33213509646).jpg

Chmee2. 2011. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prurez_stonky_lilijce_v_Dalejskym_profilu.JPG

Edna Winti. 2013. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Burgess_Shale,_Yoho_National_Park.jpg

Michael S. Engelderivative work: Kevmin. 2010. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leptofoenus_pittfieldae_(male)_rotated.JPG

Ryan Somma. 1980. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Burgess_Shale_Fossils.jpg

Helle Astrid Kjær. 2017 [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shallow_ice_core_drilling_(danish_Hans_Tausen_drill)_1.jpg

65Eq. 2017. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VostokIceCore.jpg

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio, Key and Title by uploader (Eric Fisk). 2020. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Change_in_Average_Temperature_With_Fahrenheit.svg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution.

For more bitesize content and ocean stories why not follow ‘Our world under the waves’ on…

Thank you, Matthew for these amazing insights into plant life, fish & smaller molluscs. Using the diagrams shows how the effects of climate change are accelerating and in a way I can understand.

LikeLike