by Matthew Norton

Life can be hard in the ocean. It’s a theme I’ve returned to multiple times while writing these articles, mainly because different species find different ways to meet the challenge, often through millions of years of innovation through evolution. And then you have certain animal groups who seem to have barely changed since the time of the dinosaurs, perhaps in their case natural selection decided that the old ways were the best. Horseshoe crabs are one such group who predate the dinosaurs (so far as we know) and, despite appearances, are more closely related to spiders and scorpions than ‘true’ crabs. That said, I’ll continue to call them crabs for the sake of clarity (which is probably why the name ‘horseshoe crab’ has persisted to this day).

The ‘horseshoe’ part of their name comes from the round, U-shaped head that houses most of the precious organs under a single armour plate. On the underside, the crabs have five pairs of walking legs and in front of all that there is a sixth pair of claws, called chelicerae, that work like arms for grabbing food and directing it towards the mouth. Except they have no teeth, jaws or suitable mouthparts for breaking up their food into manageable chunks. Instead they use spines at the base of their legs, called gnathobases, to crush and tenderise their food before it’s collected by the chelicerae. Think of it like squeezing an orange between your thighs.

As for defending themselves from predators, horseshoe crabs don’t seem to have much of an arsenal. They may have spines along the sides of their body, but their intimidating looking tail is primarily used for flipping themselves upright when crawling along the seabed, or steering themselves whilst swimming. The shell does effectively cover their entire body, but from personal handling experience, this layer of armour appears to be paper thin. Although this particular horseshoe crab was long dead and dried out, which may have rendered it thinner and weaker than it would otherwise be.

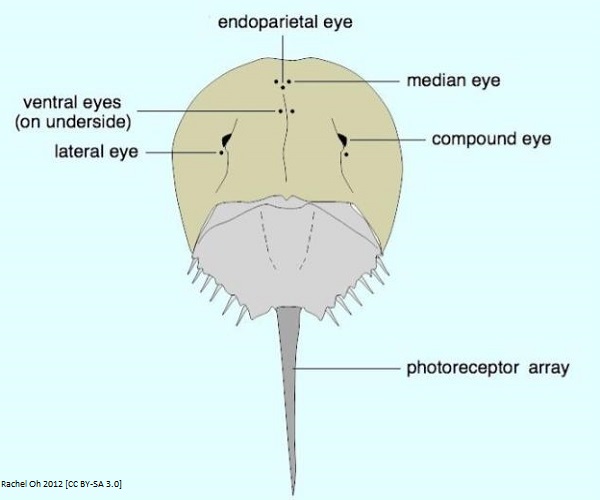

But if we look past the conventional methods of protection, we might just find that horseshoe crabs have some sly tricks up their sleeve. For example, they have ten eyes spread around their body which come in different sizes and are fitted out for different functions (see the box jellyfish article for another example). They’re mainly used for finding mates and tracking the lunar cycle, but they could also warn of approaching danger. There is also some evidence to suggest that mangrove horseshoe crabs and tri-spine horseshoe crabs possess an effective poison called tetrodotoxin to dissuade possible predators (see the pufferfish article).

Whatever defences horseshoe crabs may or may not possess, they do at least have the sense to breed in large numbers. A wise strategy given how easily distracted and vulnerable many animals can be while they’re ‘on the job’. In the case of the Atlantic horseshoe crab, they tend to gather between late spring and early summer and during the high tides. From there the males can home in on a potential mate by using their large compound eyes (relative to their other eyes and receptors), or from pheromones released by the female. But when they do actually meet, the mating process becomes an arduous process that is prone to turning into a complete farce.

The main source of contention, for the males at least, is that the eggs can only be fertilised after the female has laid them. So as far as establishing paternity is concerned, it’s a first come, first served basis with the first male endeavouring to keep his place in the queue by literally riding on the female’s back. Evolution appears somewhat skewed in the male’s favour by equipping them with specially modified claws to maintain their grip and making them only two thirds of the size of a female. Still, I’d imagine the females would tire of this burden rather quickly as they climbed up onto the beaches, ready to deposit their eggs.

Even then, a male’s success is far from assured. Over eager males may attempt to knock off a riding male, which may be what brought about the aforementioned riding claws since natural selection is bound to favour males who can hold on for longer. At the nesting site itself, there is always the chance for a few sneaky ‘satellite’ males to make their ‘contribution’ to another couple’s brood. With up to around 4,000 eggs in a single cluster, possibly accumulating to 100,000 eggs over an entire breeding season from a single female, it’s probably worth giving it a go. The sheer number of eggs might seem like an excessive effort on the female’s part, but a large proportion will be eaten by coastal seabirds such as red knots, ruddy turnstones and sanderlings.

Between their prehistoric appearance and the difficulties they face, horseshoe crabs might seem out of place in the modern world. An assumption that is unlikely to be helped by the fact that the group has only four living species to its name. And yet they persist, still able to hold their own like an ageing action hero returning to a franchise that was long thought finished. They’re still here so they must be doing something right.

From a human perspective

Like many other animals from the ocean, horseshoe crabs have been harvested for centuries to fulfil a number of our needs. Delaware Bay, on the Eastern coast of the United States, where hundreds of thousands of Atlantic horseshoe crabs come to breed, has a particularly long history of this enterprise. Reports from early European settlers state how Native Americans would catch them for food and craft them into tools and soil fertiliser. The latter ultimately led to over a million horseshoe crabs being taken and utilised as cancerine fertiliser, an industry that thrived from the 1870s to the mid 20th century. But even as this came to an end, interest grew in using horseshoe crab meat as bait for whelk pots and American eel fishing.

Moving further forward in time, horseshoe crabs have also proven useful in medicine, for within their bright blue blood there are incredibly effective immune cells called amoebocytes. Exceptionally sensitive to toxic bacteria, these amoebocytes react to their presence by creating a clot that immobilises the bacteria, isolating it from the rest of the crab’s body. This makes their blood ideal for testing vaccines, medicines and medical equipment for bacterial contamination. This is called the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) test after the Atlantic horseshoe crab or the Tachypleus amebocyte lysate (TAL) test when the blood of an Asian species is used.

The effectiveness of the LAL/TAL test is well documented, but as with all uses of horseshoe crabs, past and present, overexploitation is a serious concern. As it stands, the Tri-spine horseshoe crab is listed as “Endangered” by the IUCN, while the Atlantic horseshoe crab is “Vulnerable” and the other two species are “Data Deficient”. Proper regulation can help, but this can be difficult to achieve when you have competing interests, a lack of usable data and the interplay of fishing laws between different countries complicating matters. And let us not forget that direct fishing isn’t the only issue that horseshoe crabs have to deal with because of us humans. Climate change, pollution and habitat loss (especially on and around their nesting beaches) will pile on the pressure even more.

Fortunately, there is a work around for some of these problems. In the 1990s, a group from the University of Singapore developed a synthetic alternative to the LAL/TAL test by cloning a molecule from horseshoe crab blood. This was called Recombinant Factor C (rFC) and, in theory, it should be the perfect solution. Yet these synthetic tests are yet to be widely used in some parts of the world, perhaps because the necessary ingredients aren’t widely available, or perhaps because some countries and organisations are slow to change their practices. The USA is a notable example since at least 700,000 crabs were bled to supply LAL tests in 2021 alone.

But again, there are reasons to be optimistic. Returning to Delaware Bay, the area’s importance for nesting horseshoe crabs has not gone unnoticed. In 1999, the Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG) launched a programme to encourage local communities to declare their beaches as horseshoe crab sanctuaries. One such sanctuary (among the 16 miles worth declared) is the colourfully named Slaughter Bay, which proudly displays its status on their official government website. If Atlantic horseshoe crabs are considered with such adoration and pride in an area so critical to their survival, then surely there is hope for the future of their species.

But the reason behind the name has long been debated between with a number of different origins. These stories include a postmaster with the surname “Slaughter” and nearby creeks and towns (from old maps) with Slaughter in their name. The most disturbing possibility involves the massacre of a group of Native Americans by cannon fire.

As marvellous as horseshoe crabs are, the protection they need isn’t just for their sake. There are plenty of animals that rely on them for food, from small fish and hermit crabs to sharks and loggerhead turtles. Their eggs are also a crucial food source for migrating birds like rufa red knots, who might not even make it to the Canadian Arctic tundra without this crucial fuel stop. Even the shell of a horseshoe crab can provide a hard surface for animal like barnacles and slipper limpets to hang on to while their digging activities can rework and refresh the seafloor to the benefit (or detriment) of other species. No species in this world can live in complete isolation, not even us.

Sources

Wikipedia. 2023. Horseshoe crab. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horseshoe_crab#. Last accessed 11/07/2023

The National Wildlife Federation. Horseshoe Crab. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Horseshoe-Crab. Last accessed 11/07/2023

Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. 2022. 10 Incredible Horseshoe Crab Facts. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/news/10-incredible-horseshoe-crab-facts. Last accessed 31/07/2023

Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Horseshoe Crab Anatomy. https://dnr.maryland.gov/ccs/Pages/horseshoecrab-anatomy.aspx. Last accessed 31/07/2023

Kungsuwan et al. 1987. Tetrodotoxin in the horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda inhabiting Thailand.

Brockmann. 1990. Mating behavior of horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus

NOAA. 2018. Horseshoe Crabs: Managing a Resource for Birds, Bait, and Blood. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/horseshoe-crabs-managing-resource-birds-bait-and-blood. Last accessed 08/08/2023

Kreamer and Michels. 2009. History of horseshoe crab harvest on Delaware Bay

Krisfalusi-Gannon et al. 2018. The role of horseshoe crabs in the biomedical industry and recent trends impacting species sustainability

Pavid. 2021. Horseshoe crab blood: the miracle vaccine ingredient that’s saved millions of lives. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/horseshoe-crab-blood-miracle-vaccine-ingredient.html. Last accessed 31/07/2023

Gauvry et al. 2022. LAL/TAL and Animal-Free rFC-Based Endotoxin Tests: Their Characteristics and Impact on the Horseshoe Crab Populations in the United States and Asia

Eisner. 2023. Coastal biomedical labs are bleeding more horseshoe crabs with little accountability. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/10/1180761446/coastal-biomedical-labs-are-bleeding-more-horseshoe-crabs-with-little-accountabi. Last accessed 31/07/2023

John et al. 2021. Conservation of Asian horseshoe crabs on spotlight

Wang et al. 2020. Future of Asian horseshoe crab conservation under explicit baseline gaps: A global perspective

IUCN Red List. https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?query=horseshoe%20crab&searchType=species. Last accessed 29/08/2023

Maloney et al. 2018. Saving the horseshoe crab: A synthetic alternative to horseshoe crab blood for endotoxin detection

Berkson and Shuster Jr. 1999. The horseshoe crab: the battle for a true multiple‐use resource

Delaware Government Information Centre. History. https://slaughterbeach.delaware.gov/history/. Last accessed 08/08/2023

Delaware.gov. 2022. FAQs about Delaware Bay Rufa Red Knots and Horseshoe Crabs. https://documents.dnrec.delaware.gov/fw/conservation/Del-Bay-Red-Knot-Horseshoe-Crab-FAQ.pdf. Last accessed 08/08/2023

The Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG). Backyard Stewardship™: Coastal Communities Define Their Shared Habitat as a Horseshoe Crab Sanctuary. https://www.horseshoecrab.org/act/sanctuary.html. Last accessed 08/08/2023

ecoDelaware. Slaughter Beach, an official horseshoe crab sanctuary. http://www.ecodelaware.com/place.php?id=358#:~:text=Slaughter%20Beach%20is%20an%20ERDG,an%20official%20Community%20Wildlife%20Habitat. Last accessed 08/08/2023

Florida fish and wildlife conservation commission. Facts About Horseshoe Crabs and FAQ. https://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/crustaceans/horseshoe-crabs/facts/#:~:text=Many%20fish%20species%20as%20well,%2C%20horse%20conchs%2C%20and%20sharks. Last accessed 08/08/2023

Botton. 2009. The ecological importance of horseshoe crabs in estuarine and coastal communities: a review and speculative summary

Image sources

James St. John. 2013. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Limulus_polyphemus_(Atlantic_horseshoe_crab)_(Sanibel_Island,_Florida,_USA)_2.jpg

Alexander Hüsing from Berlin, Deutschland. 2007. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesolimulus_walchi.jpg

Rhododendrites. 2017. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_crab_in_Silver_Sands_State_Park_(21090).jpg

Gee. 2017. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_Crab_chelicerae_and_gnathobases.jpg

Rachel Oh. 2012. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_crab_eyes.jpg

Rhododendrites. 2019. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_crabs_mating_(57352).jpg

Marshall Astor from San Pedro, United States. 2007. [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_Crab_in_Si_Racha.jpg

Decumanus. 2004. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Delaware_bay_map.jpg

DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS). 2022. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:202210_Tri-spine_horseshoe_crab_donating_blood.svg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution.

For more bitesize content and ocean stories why not follow ‘Our world under the waves’ on…