by Matthew Norton

Since the beginning of Our World Under The Waves, I’ve tried to reflect the variety of the world’s sea creatures by introducing obscure animal groups, covering well-known species (e.g. pufferfish) from unusual angles, and everything in between. But it’s a big ocean out there, and even with 50+ articles to my name, I am guilty of more than a few oversights. For instance, all articles published under the “Big fish” category have been about sharks. Impressive though they are, sharks are not the only fish in the sea, so let’s give the big bony fish some time to shine, starting with the aptly named Giant Grouper.

They may also use slight fin movements to maintain their position while hovering in mid-water.

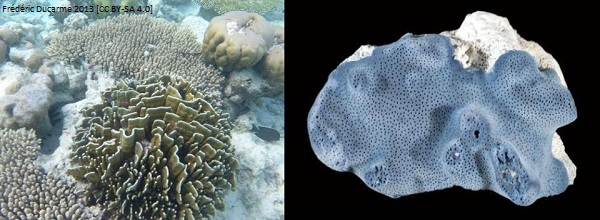

Able to grow to at least 2.7 metres long, weighing in at around 400kg (though some claim that stretch further to 3 metres and 600kg), giant groupers are one of the largest bony fish in the world. And probably the largest fish you could hope to see around the tropical coral reefs on the Indo-Pacific and around Australia, where they’re commonly known as Queensland groupers. You may also find them in underwater caves, wrecks and harbours, if you’re so inclined to look. But be warned, they are territorial animals and are known to attack interlopers if sufficiently provoked, although posturing and low frequency warning sounds are enough to settle most disputes, with no prolonged violence necessary.

Small animals would be especially wise to give these big fish a wide berth, given their tendency to take a wide variety of prey, including bony fish, molluscs, crabs, spiny lobsters (reported by some to be their favourite food), rays, sharks and even sea turtles. For the latter three, giant groupers would typically only pounce on the smaller species, or the smaller juveniles of large species. That said, their mouths can, and will, stretch wide open to engulf their meal and swallow it whole, aided by the small, but sharp canine teeth. A rather gruesome fate for anyone who fails to evade them.

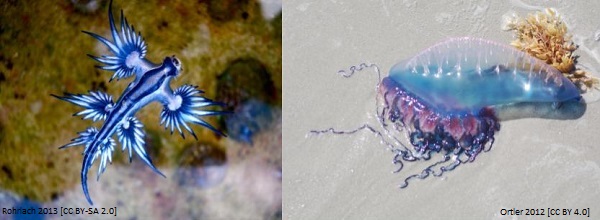

And yet, there is a small fish (one scarcely bigger than your finger) who will not only swim up to a giant grouper, but willingly slip into their mouth and work their way around the big fish’s teeth as required. Such is the bold lifestyle of a bluestreak cleaner wrasse who, despite how dumb their behaviour may sound, is actually one of the smartest fish in the world, smart enough that the giant grouper is very unlikely to eat them. Why would the grouper deprive itself of the invaluable cleaning service provided by the wrasse? Why risk being overrun by ectoparasites (i.e. parasites who attach themselves to the outside of their host) and anything else they may wish to be removed, in exchange for such a pitifully small meal?

Bluestreak cleaner wrasse are smart enough to not push their luck however. With other ‘clients’ they may be inclined to cheat by removing the fish’s scales, or biting into the mucus of their mouth instead of the parasites they were supposed to be clearing away. But they know the difference between the small residential fish they can risk ripping off, and the big predators who may retaliate with something far worse than a bad review on Trip Advisor. Naturally, giant groupers fall into the latter category, their colossal size ensuring that they have little to fear from the world around them.

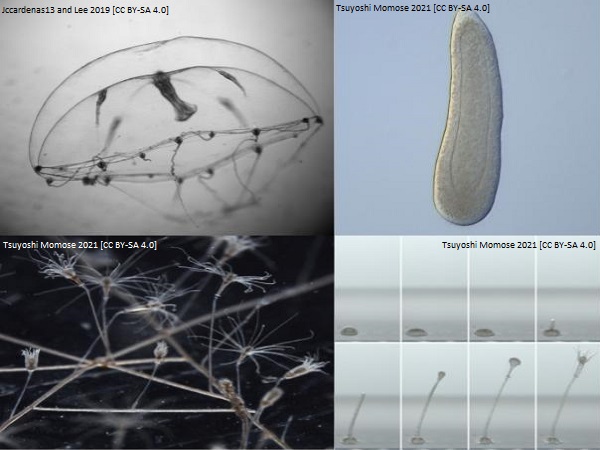

But for young giant groupers, life carries a considerably greater risk of being attacked and/or eaten. As tiny giant grouper fry, they may not even be safe among their own kind according to research with individuals reared in aquarium conditions. Find yourself with grouper fry bigger than you (at least 30% bigger according to one study) and you may be considered easy pickings.

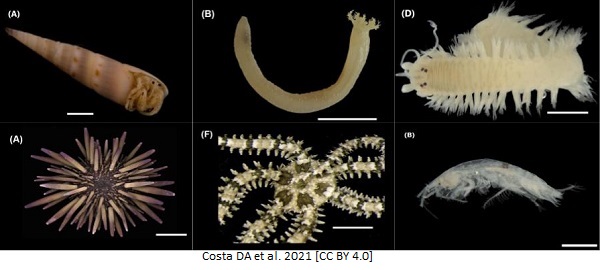

As for well developed juveniles, though not longer the diddy little fry they once were, are still going to be vulnerable to large predators until they attain the substantial size of an adult giant grouper. This may explain why their colours are so different, bearing irregular splashes of yellow and black instead of the mottled grey of fully formed adults. “May” being the key word here, for my attempts to find out the purpose behind these particular childhood colours have been fruitless (at the time of writing). But I can speculate on two possible explanations, based on the adaptations of other fish species.

Maybe the black and yellow colours protect juvenile giant groupers by mimicking the patterns of creatures who are poisonous, venomous or capable of inflicting nasty wounds in self-defence. This would be an example of ‘Batesian mimicry’, a tried and tested strategy employed by the juveniles of other large fish and those who remain small into adulthood.

The baby harlequin sweetlips (Plectorhinchus chaetodonoides; top left) both looks and moves like a toxic flatworm or nudibranch.

The baby zebra shark (Stegostoma tigrinum; top right) has black and white stripes to mimic a banded sea krait (Laticauda colubrina), which has nasty venom in its fangs.

The comet fish (Calloplesiops altivelis; bottom right), when it senses danger, sticks its face into the rock and arranges its body and fins and to resemble the head of a whitemouth moray eel (Gymnothorax meleagris) complete with a fake eye spot on both sides.

The sabre-tooth blenny, also known as the false cleaner wrasse (Aspidontus taeniatus; bottom left), who just bites off pieces of client fish, using their resemblance to aforementioned bluestreak cleaner wrasse to approach big fish unharmed.

Or, the black and yellow pattern may serve as the ideal camouflage for a juvenile grouper, according to their size, lifestyle, habitat, or combinations therein. The latter is particularly worth considering, since many species in the sea do use ‘nursery habitats’ (e.g. mangrove forests, seagrass beds) where the young will find relative safety compared to the habitat occupied by their parents. However, these nurseries (sheltered though they may be) can also present challenges that would only impact the fish during these formative years, requiring adaptations that need only be expressed during that particular period.

See for yourself: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pS63liVRyc

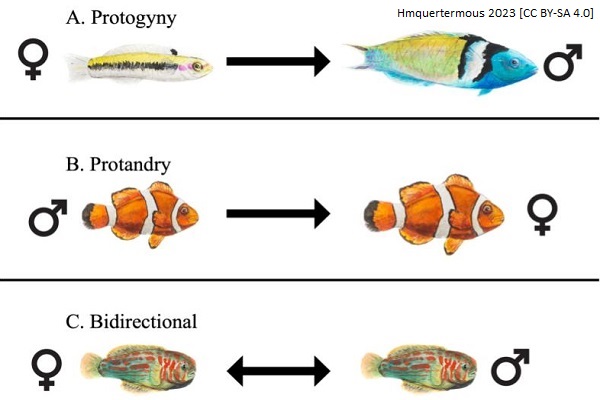

Whatever the case may be, the mottled grey colouration will eventually emerge as the giant grouper enters adulthood. But that doesn’t mean they’ve finished changing, far from it, since giant groupers also engage in protogynous hermaphroditism, meaning that the females (at some point after reaching maturity) can turn into males. It’s an ability that’s shared among the various species of grouper and is surprisingly common among fish in general, though it can go from male to female (protandrous hermaphroditism) instead, depending on the dynamics of the species. For example, going from female to male would suit species where the males need to be large to have even a fighting chance of competing for a mate. But going from male to female might suit other species by allowing the larger females to invest significantly more resources and energy in each batch of young. And in the case of the giant grouper there is the added complication of some males starting out as males straight away, skipping the change altogether. A phenomenon known as diandric protogynous hermaphroditism.

And for giant groupers, there is the matter of diandric protogynous hermaphroditism, where there are two versions (or phenotypes) of a male, those who mature as females and then later transform into males, and those mature as males (skipping the female stage entirely). As opposed to monandric protogynous hermaphroditism, where there is only one version of a male (i.e. the one that matures as a female first).

Assuming all goes well, and the giant grouper doesn’t starve, get eaten or otherwise dispatched before they reach maturity (in one form or another), they should get the opportunity to breed and pass on their genes to the next generation. But even this biblical act can take an unexpected turn with giant groupers sometimes mating with groupers of other species to produce hybrid offspring. It’s a twist that may occur naturally, in the wild, but it seems to be particularly prevalent in the aquaculture industry, typically with the giant grouper being the father.

Sometimes, this is achieved by simply introducing the male of one species and the female of another to the same tank and encouraging them to do the deed. Sometimes, our interventions are more clinical, with artificial insemination and cryopreserved (i.e. frozen) sperm being used to achieve the desired result. And sometimes, these hybrids are quite beneficial for the trade into which they were conceived, producing individuals who can grow faster, produce more meat and be more resilient to disease and hypoxia (low oxygen conditions that can occur whilst keeping and transporting live fish) compared to one or both of their parent species. But then there’s the risk of reaping what you sow, as proven by the Hulong hybrid grouper, produced by crossing giant groupers with tiger groupers, who proved resilient enough to become an invasive species in the wild, specifically off the coast of Hainan Island, China.

Hybridisation is a curious thing in general, usually producing offspring who are sterile (and thus unable to pass on their genes to the next generation), beset with deformities or other health problems, or were never viable to begin with. So why would giant groupers, or any other fish for that matter, cross that species barrier at all? Perhaps both mother and father don’t realise they’re not of the same species, especially if their species are closely related. Even we have trouble identifying species with absolute certainty (and last I checked, giant groupers don’t have access to binoculars and ID guides). Perhaps the doubts are there during their brief encounter, but they decided to do it anyway. Because what would be the greater risk? Mating with the wrong partner, or rejecting the right one? And in some cases the union can work, perhaps going as far as to kickstart a brand species.

All things considered, the life of a giant grouper isn’t all about growing big and strong, there are other changes to go through, timings to finesse and decisions to make that could greatly impact how long they survive and what they leave behind once they’ve the exhausted the last of their fleeting moments on planet Earth. Boldness can be dangerous if enacted at the wrong moment, but sometimes playing it safe isn’t an option either.

From a human perspective

They may not be sharks, but giant groupers are still big, powerful fish that inspire awe in most, if not all people who come across them. Those of a certain mindset would see them as a worthy challenge to be overcome at the end of a fishing rod or a speargun.

This was once the case in New South Wales, Australia, where giant groupers were popular targets for anglers and spearfishers until they were listed as a protected species under the Fisheries Management Act 1994. In my experience (such as it is from speaking to a few local anglers) catch-and-release fishing is already pretty common among recreational anglers, but with giant groupers caught in NSW waters, it is a legal requirement. One would imagine the thrill of the chase, and the effort of unhooking such a colossal creature, would be more than enough, as evidenced by their appearance on an episode of Jeremy Wade’s River Monsters. Giant groupers aren’t exactly river fish, nor was it the fish he was after, but I doubt the viewers were complaining.

Still, the hope is that aquaculture will minimise the need to take from wild populations, and therefore reduce the risk of overfishing. The ethics of the practice is another matter however, and one would hope that the floating cages, ponds, live transport vessels, and other set-ups are suitable for them during their farmed lives.

Some claim that giant groupers have got their own back on being hunted and/or handled from time to time. The species has even been implicated in fatal attacks, though as far as I can tell, none of them have been fully documented or confirmed. Physically, they are capable of the act and are reported to be curious of people from time to time, while the similarly large Goliath grouper is known to stalk divers and sometimes attempt (usually unsuccessful) ambushes. And there have been confirmed non-fatal attacks, such as an incident that occurred on New Year’s Eve, 2001, when a giant grouper (believed to be around two metres long and 80 years old) attacked a Swedish diver near the wreck of the steamship Yongala, located 100km southeast of Townsville, Australia.

It was the kind of rare incident that would inspire debate around the potential cause. For example, the Florida based Marine Safety Group (MSG) suggested, based on what they had seen at dive sites closer to home, that people feeding these large, predatory fish may have been a contributing factor. Although, there was a general code of conduct among the operators who led dive tours to the Yongala wreck that there was to be no feeding of the animals. Maybe there was an operator or two who were secretly breaking that rule, maybe someone was altering the grouper’s behaviour in some other way without realising. Or maybe the grouper was feeling particularly territorial and this particular diver was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Whatever the case, you should generally be okay around groupers (and other large reef predators) so long as you stay calm, respect their boundaries and don’t try to force any interactions or unnatural behaviours. And that should include conditioning them (intentionally or otherwise) to expect free handouts.

Of course, not all interactions between humans and giant groupers take place in the ocean, or at the end of a line. The latter can also be found behind a thick layer of glass, for groupers are quite popular in public aquariums, with the larger species certainly making their presence known if and when they choose to approach the window. What often surprises visitors, once the shock of their sheer size has passed, is the lack of any attempt to hunt the smaller fish living in the same exhibit. Spoiler alert, aquariums tend to keep large predatory fish well fed, at least well fed enough that they don’t need to hunt, as well as providing the necessary supplements to meet their vitamin and mineral needs.

And the care that a giant grouper can expect within aquarium waters extends well beyond just feeding them, as demonstrated by the story of ‘Bubba’. First introduced to the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, USA in 1987, via a large bucket left at reception, the 25cm (10 inch) long female ultimately grew to 1.37 metres, and weighed around 69kg, as well changing gender along the way. If there were any doubts that she (then he) was a hit among visitors, they were firmly smashed by uproar of his temporary move off-display in 1998. But then in 2001, pink pimply growths were noticed on his head which, at first, was mistaken for a bacterial infection. The subsequent course of antibiotics proved ineffective however, with a couple of biopsies revealing he actually had cancer.

Such a diagnosis would be game over in the wild, but Bubba was in a uniquely fortunate position and by autumn 2002 the veterinarians at the Shedd Aquarium, along with veterinary oncologists from further afield, surgically removed the tumours and administered chemotherapy. So far as is known, he was the first fish to receive a full course of chemotherapy and beat cancer.

The success was unfortunately short-lived, with the cancer returning by Spring 2003, requiring a more aggressive procedure where bigger chunks of flesh were removed and connective tissue implants were needed to bridge the gaps. It would have taken great skill to perform an operation like this, but even those pioneering surgeons couldn’t get around the impossibility of keeping a dry bandage on a fish. Fortunately, Bubba himself had this covered, producing a natural layer of mucus that coated his entire body and which was swarming with antibodies for fighting infection. And he was able to do this while undergoing more chemotherapy, this time directed around the edges of where the tissue had been removed, to catch any malignant tumour cells that might have survived the purge. It would have been a long, and at times stressful, ordeal, but it gave Bubba an extra three years of life until his sudden passing in 2006 at the age of 24.

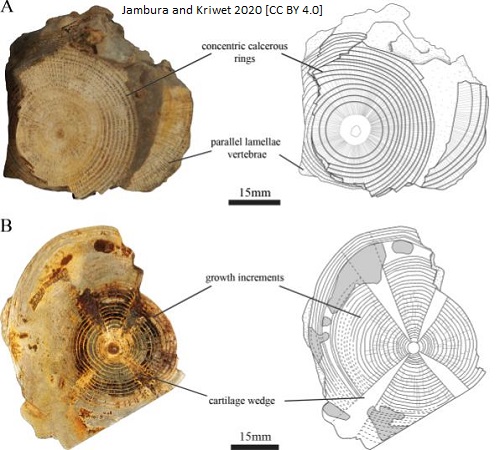

Your best bet for seeing Bubba’s actual remains is the Field Museum in Chicago, which has his skeleton as part of their large fish collection as well as cryogenically frozen tissue samples.

It goes without saying that none of this treatment would’ve been available to Bubba in the wild, and it would’ve been more natural to simply allow him to succumb to the disease. Then again, even the largest and best equipped aquariums in the world cannot make the lives of their animals 100% natural. What they can do is provide these animals with suitable food, habitat and stimulation to ensure they can live long, contented lives in an aquarium environment. This would include a ton of intensive research and planning to ensure they can feasibly take on a given animal in the first place, but when it comes to the day-to-day operation, the means of achieving the above can be fairly simple. These include providing different foods on different days (if applicable to their natural diet), appropriate hiding places for cave dwelling animals (e.g. octopuses and conger eels) and novel objects (including toys) for especially inquisitive animals to investigate and interact with. And for the big animals, they may be trained to recognise a given target and associate it with food. For Bubba, Shedd Aquarium used a blue triangle, while at the aquarium where I work (which I appreciate can make me seem a little biased) we’ve used yellow balls on sticks and black and white patterns painted on boards. It’s a practice that ensures the big fish do get their food and don’t start snacking on their smaller tank mates instead. It also creates opportunities for aquarium staff to conduct health checks, without chasing the animals and stressing them out, and to make the animals work for their food by chasing the target, thus adding another level of stimulation.

I should say, as a general disclaimer, that when it comes to big animals there are species who cannot adapt to living in an aquarium and so should not be kept in one. In particular, very large animals who migrate over vast distances, such as whales, dolphins and some sharks, need more space and social contact than an aquarium tank can realistically provide. And unfortunately, despite the high level of care they provided for Bubba, Shedd Aquarium, by keeping beluga whales and Pacific white-sided dolphins, has yet to move away from this particular ethical minefield.

But where it is possible, and ethical, to keep large and impressive sea creatures in an aquarium environment, there is little doubt about the huge role they play in introducing the general public to the marine world. Mainly because it’s a world that is difficult to access in the ocean itself, given that many creatures (including big fish like Porbeagle sharks) would be compelled to hide, swim or crawl away if they saw a human swimming their way. And that’s assuming you know where to find them in the first place. Don’t get me wrong, it can be done, and the reward of experiencing the ocean’s marvels firsthand, and in their own domain, is second to none. But frankly, going to see them in an aquarium is so much easier and still brings about so much joy, especially to young children (see Starfish article).

Again, this is dependent on the animals being properly cared for, which sometimes requires medical interventions that would not happen in the wild. It also makes practical sense to keep these animals happy, healthy and alive for as long as is reasonably possible (without denying them euthaniasia if it’s the kindest thing to do) so that fewer of them need to be removed from the wild. Especially with species who are difficult, if not impossible to breed in an aquarium environment for one reason or another.

On the public engagement side, the story of a popular resident recovering from a nasty injury, or a serious illness, is a great story to tell and one that often makes the animal more relatable with visitors and animal enthusiasts further afield. In the case of Bubba the giant grouper, his brush with cancer made him an inspiration to adults and children (especially children) who had gone through, or were going through the same difficult journey. This led to numerous phone calls from patients and their families to ask how Bubba was doing and even a recognition tile at Hope Children’s Hospital in Oak Lawn, Illinois.

And this particular giant grouper is just one of many prime examples of how meeting marine life, even in an aquarium environment, can really build that human connection. In my local aquarium alone, there is a large humphead wrasse who likes to lurk from behind rocks and generally people watch, a conger eel who sleeps upside down in her cave and an adorable small-spotted cat shark who turned two years old on the day this very article was published. Long story short, the more you become acquainted with these animals, the more you realise that they are not just a member of their species, they are individuals with their own quirks and personalities. Maybe not exactly the same way we do, but close enough to be worth certain considerations.

Sources

McGrouther. 2021. Queensland Groper, Epinephelus lanceolatus (Bloch, 1790). https://australian.museum/learn/animals/fishes/queensland-groper-epinephelus-lanceolatus-bloch-1790/. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Bray. 2021. Queensland Groper, Epinephelus lanceolatus (Bloch 1790). https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/4672. Last accessed 19/11/2025

FishBase. Epinephelus lanceolatus (Bloch, 1790)

Giant grouper. https://fishbase.se/summary/6468. Last accessed 19/11/2025

New South Wales (NSW) Government. Giant Queensland groper. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/closures/identifying/marine-or-estuarine-species/giant-queensland-groper. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Nausicaá Boulogne-sur-mer. Giant Grouper. https://www.nausicaa.fr/en/my-visit/animals/giant-grouper. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Aquarium of the Pacific. Queensland Grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/queensland_grouper. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Myoung et al. 2013. First Record of the Giant Grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus (Perciformes: Serranidae: Epinephelinae) from Jeju Island, South Korea

Brewster et al. 2023. Seasonal Dynamics and Environmental Drivers of Goliath Grouper (Epinephelus itajara) Sound Production

Singapore Oceanarium. Giant Grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus. https://www.singaporeoceanarium.com/en/animals-habitats/animals-a-z/giant-grouper.html. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Science Source. Wrasse cleaning the teeth of a Grouper – Image. https://www.sciencesource.com/1145494-wrasse-cleaning-the-teeth-of-a-grouper-stock-image-royalty-free.html. Last accessed 25/10/2025

Guy. 2016. On Certain Mental Tests, the Tiny Cleaner Wrasse Outperforms Chimps. https://oceana.org/blog/certain-mental-tests-tiny-cleaner-wrasse-outperforms-chimps/. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Hugh. 2019. Cleaner Wrasse “Clean” a Grouper. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/blogs/comments/cleaner_wrasse_clean_a_grouper. Last accessed 19/11/2025

Hseu et al. 2004. Morphometric model and laboratory analysis of intracohort cannibalism in giant grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus fry

Spencer. 2021. How Animals Mimic Each Other to Survive and Thrive. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2021/03/15/mimicry/. Last accessed 08/11/2025

FishBase. Calloplesiops altivelis (Steindachner, 1903)

Comet. https://www.fishbase.se/summary/Calloplesiops-altivelis.html. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Shark Trust. 2020. CREATURE FEATURE: Zebra Shark. https://www.sharktrust.org/blog/creature-feature-zebra-shark. Last accessed 22/10/2025

McGrouther. 2019. Spotted Sweetlips, Plectorhinchus chaetodonoides Lacépède, 1801. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/fishes/spotted-sweetlips-plectorhinchus-chaetodonoides/. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Bray. 2020. Round Batfish, Platax orbicularis (Forsskål 1775). https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/2208. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Andrew Mitchell. 2017. MangroveLeafFish. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pS63liVRyc. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Palma et al. 2019. Reproductive development of the threatened giant grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus

University of the Sunshine Coast. 2021. Study finds surprising sex change secrets of giant grouper. https://www.usc.edu.au/about/unisc-news/news-archive/2021/march/study-finds-surprising-sex-change-secrets-of-giant-grouper. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Florida Museum. 2025. Goliath Grouper. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/100-years/object/goliath-grouper/. Last accessed 08/11/2025

Chen et al. 2020. A highly efficient method of inducing sex change using social control in the protogynous orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides)

Quertermous and Gemmell. 2024. Sex change in fish

The Wildlife Trusts. Cuckoo wrasse. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/marine/fish-including-sharks-skates-and-rays/cuckoo-wrasse. Last accessed 25/10/2025

FishBase. Rhinogobiops nicholsii (Bean, 1882) Blackeye goby. https://fishbase.se/summary/3847. Last accessed 25/10/2025

Casas et al. 2016. Sex change in clownfish: molecular insights from transcriptome analysis

FishBase. Sparus aurata Linnaeus, 1758 Gilthead seabream. https://www.fishbase.se/summary/Sparus-aurata.html. Last accessed 25/10/2025

Zhang et al. 2024. The Hulong hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀×Epinephelus lanceolatus♂) has invaded the coastal waters of Hainan Island, China

Shapawi et al. 2018. Nutrition, growth and resilience of tiger grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus) × giant Grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) hybrid‐ a review

Kiriyakit et al. 2011. Successful hybridization of groupers (Epinephelus coioides x Epinephelus lanceolatus) using cryopreserved sperm

Huang et al. 2014. Characterization of triploid hybrid groupers from interspecies hybridization (Epinephelus coioides ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂)

Masuma and Aoki. 2023. Maturation in a hybrid grouper, Kue-Tama, a cross between female longtooth grouper, Epinephelus bruneus, and male giant grouper, E. lanceolatus

Gong et al. 2025. Development and characterization of a novel intergeneric hybrid grouper (Cromileptes altivelis♀× Epinephelus lanceolatus♂)

Wang et al. 2024. Acute hypoxia and reoxygenation alters glucose and lipid metabolic patterns in Hulong hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀× E. lanceolatus♂)

River Monsters™. 2024. Jeremy Wade catches a HUGE 250lbs+ Queensland GROUPER by accident | River Monsters. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFvQcRXNDJM. Last accessed 28/11/2025

Glamuzina and Rimmer. 2002. Grouper aquaculture world status and perspectives

Southeast Asian Fisheries Department Centre / Aquaculture Department (SEAFDEC/AQD). Quality seed for sustainable aquaculture. https://www.seafdec.org.ph/thematic-areas/quality-seed-for-sustainable-aquaculture/. Last accessed 28/11/2025

Russo. 2014. Think Sharks Are Scary? This Goliath Grouper Attack Is Terrifying. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/goliath-grouper-attack_n_5632612. Last accessed 28/11/2025

CYBER DIVER News Network. 2002. Did fish feeding cause recent shark, grouper attacks?. https://web.archive.org/web/20021026164337/http://www.cdnn.info/eco/e020104/e020104.html. Last accessed 25/10/2025

Troy Mayne. 2016. Queensland Groper Attack on the Yongala Wreck, Great Barrier Reef. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hM3XyuT8zBs. Last accessed 28/11/2025

Underwater Times. 2006. ‘Bubba,’ Famed Cancer-surviving Grouper, R.I.P.; ‘Overcame Some Incredible Odds’. https://www.underwatertimes.com/news.php?article_id=71021389645. Last accessed 04/12/2025

Gross. 2025. Gigantic “super grouper” named Bubba becomes first fish to survive chemotherapy. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2025/3/gigantic-super-grouper-named-bubba-becomes-first-fish-to-survive-chemotherapy. Last accessed 04/12/2025

Shedd Aquarium. 2006. Bubba: Super Grouper. https://web.archive.org/web/20060930110139/http://www.sheddaquarium.org/bubbasupergrouper.html. Last accessed 04/12/2025

Shedd Aquarium. Animals. https://www.sheddaquarium.org/animals. Last accessed 04/12/2025

Cameron et al. 2018. Transatlantic movement in porbeagle sharks, Lamna nasus

Image sources

Ginkgo100. 2006. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GiantGrouper018.JPG

Rob and Stephanie Levy. 2008. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pharynx_and_Gill_raker_of_Epinephelus_coioides.jpg

Elias Levy. 2012. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bluestreak_Cleaner_Wrasse_(6997583331).jpg

Citron. 2014. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Epinephelus_lanceolatus_young.jpg

K. Picard, M. Stowar, N. Roberts, J. Siwabessy, M.A. Abdul Wahab, R. Galaiduk, K. Miller, S. Nichol. 2021. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Epinephelus_lanceolatus_Money_ShoalCaptureFig32Picard.png

Gp258. 2016. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zebra_Shark_Baby.jpeg

Longdongdiver (Vincent C. Chen). 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Calloplesiops_altivelis_%E7%91%B0%E9%BA%97%E4%B8%83%E5%A4%95%E9%AD%9A.jpg

Rickard Zerpe. 2017. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harlequin_sweetlips_juvenile_(Plectorhinchus_chaetodonoides)_(35635869076).jpg

Izuzuki. 2005. [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NiseKGP.jpg

Chaloklum Diving. 2014. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Platax_orbicularis_juvenil.jpg

Hmquertermous. 2023. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sequential_hermaphroditism_systems.png

Libbykeatley. 2024. [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Labrus_mixtus_N_Ireland_male.jpg

Brian Gratwicke. 2009. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rhinogobiops_nicholsii;_Blackeye_goby.jpg

Jenny from Taipei. 2006. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clownfish_(Amphiprion_ocellaris).jpg

Roberto Pillon. 2011. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sparus_aurata_Sardegna.jpg

RuchaKarkarey. 2015. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brown_marbled_grouper_(Epinephelus_fuscoguttatus)_Lakshadweep.jpg

Totti. 2020. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Epinephelus_bruneus_AQUAS.jpg

Aleksey77Smirnov. 2010. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SpearfisherMonument.jpg

Peachyeung316. 2022. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Fresh_Giant_grouper_brindle_bass_on_the_Seafood_Shop_in_Yan_Oi_Market.jpg

Better days came. 2013. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queensland_grouper.jpg

All other images are public domain and do not require attribution,